By: Jeanette Tong

Recently in his New Year’s address, Xi Jinping proclaimed a plan to revive the economy. The State Council Information Office held a press conference on the “Achievements of China’s High-Quality Economic Development,” briefing the public on the results of China’s comprehensive economic development in 2024. Recently, the National Bureau of Statistics announced that China’s GDP grew by 5% throughout 2024, exactly meeting the projected target. All these moves created a false impression to those in the outside world that still willing to believe it that China’s economy is still quite resilient.

China’s economic boom over the past few decades was driven by the contributions of a vast number of private-sector business owners. They were once full of hope and , therefore working diligently to create extraordinary wealth for themselves and their country. They provided more than 60% of China’s GDP and 90% of its employment. Now, when a large number of private entrepreneurs and senior executives of listed companies have been detained or have disappeared—and when those who are still free choose to lie low and do nothing—the 5% growth figure inevitably raises doubts.

With the Chinese New Year approaching, many entrepreneurs will not be able to reunite with their families. They would never have imagined that, having once been honored guests of the government due to their success, they are now being illegally detained, and their wealth expropriated, precisely because of that success and wealth.

Because local finances across China are under severe strain, the economic stimulus and debt-reduction measures introduced by Beijing can be described as a mere drop in the bucket. Even the latest official data show that these measures are completely unable to boost people’s willingness to consume or investment, nor can they mitigate the serious local-government debt crisis. Beijing has made it clear that local authorities must figure out solutions themselves to handle their debt—“You raise your own child.” This means heavy debt-repayment pressure remains on local governments. Under these circumstances, in recent years, to fill budget gaps caused by economic decline, local governments have resorted to the widespread practice of “profit-driven law enforcement” across provincial borders— so-called “distant-water fishing,” the growing practice of trying to grab money from people from other parts of China arrested in-province and held in detention centers (“liuzhi centers, 留置中心”) illegally repurposed for that task by brutal local governments. The police are the fishermen going out to sea, and wealthy entrepreneurs are the fish in the net, defenseless. Large numbers of business owners from other regions have been taken away by police on trumped-up charges, with their corporate or personal bank accounts and assets illegally frozen or seized. In mere minutes, hundreds of millions of yuan in assets—earned through the entrepreneurs’ years of hard work—can be openly plundered without any legal protection.

Besides the recently reported CNN cases of traceable detention centers, many hotels and guesthouses in third- or fourth-tier cities and remote county towns have also been rapidly converted into makeshift ones, Their windows are boarded up; small 10-square-meter rooms are lit 24 hours a day; two or three auxiliary police officers watch the detained entrepreneur around the clock. Walls, floors, restroom facilities, and even ceilings have been refitted to “prevent suicide.” Soft anti-collision padding has even become a hot commodity in the building-materials market! If you search online for “liuzhi center staff recruitment,” you’ll see that in a sluggish economy with high unemployment, these detention-center auxiliary-police jobs are suddenly in demand, as the police need a large workforce to assist in this massive, blatantly open wealth-grab operation.

The walls and furniture in the interrogation rooms for entrepreneurs must be equipped with suicide-prevention soft anti-collision padding.

Including all these refurbished buildings, China now definitely has more than a thousand such liuzhi centers to detain business owners, and the number of those who are or have been detained runs into the hundreds of thousands. These are arguably the elite of Chinese society, the most critical drivers of China’s economic development. When younger, they experienced the era of reform and openness, themselves adopted relatively open, universal values, and benefited from China’s economic boom through their own hard work, achieving great success. They could never have anticipated the country’s sudden policy U-turn, and the economic downturn that followed. Once contributors to the national economy and honored guests of senior government officials, they have in just a few short years become prisoners.

CNN’s Xiong Yong’s recently filed an article describing the abuse these entrepreneurs suffer while in custody. He writes:

“The Chinese lawyer who represented officials in court after they were released from liuzhi custody said it was common for detainees to be forced to sit in one position for up to 18 hours a day.

‘They had to sit continuously without moving, causing severe pressure ulcers on their buttocks. Some medicine would be applied, but they were made to keep sitting, leading to further deterioration. It was extremely torturous,’ they said.

Some clients were also given very little food until they confessed, causing malnutrition and a host of other health problems, the lawyer said. ‘Many people eventually developed auditory hallucinations and felt like they were losing their minds,’ they said.”

After three to six months of detention—sometimes even longer—the entrepreneurs either pay a huge fine to buy back their freedom or remain detained indefinitely. In a society where the authorities are not subject to law, only what the Party decides today that it wants, everyone faces uncertainty, since Party decisions can change with the mood of the current (quite well-nourished) dictator. Policy reversals can wipe out large groups of individuals and even entire industries in just a few days. How could entrepreneurs who have endured inhumane abuse forget such a terrifying ordeal and then, like robots, continue to serve this perverse and terrifying country simply because the “great leader” waves his arm to signal them? Disheartened entrepreneurs have instead determined that a short-term recovery of the private economy is impossible. Their capital has been illegally seized; their businesses have been persecuted; and, more importantly, their spirits have been crushed by the vast and merciless Party-state machine.

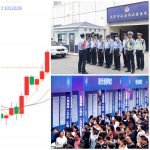

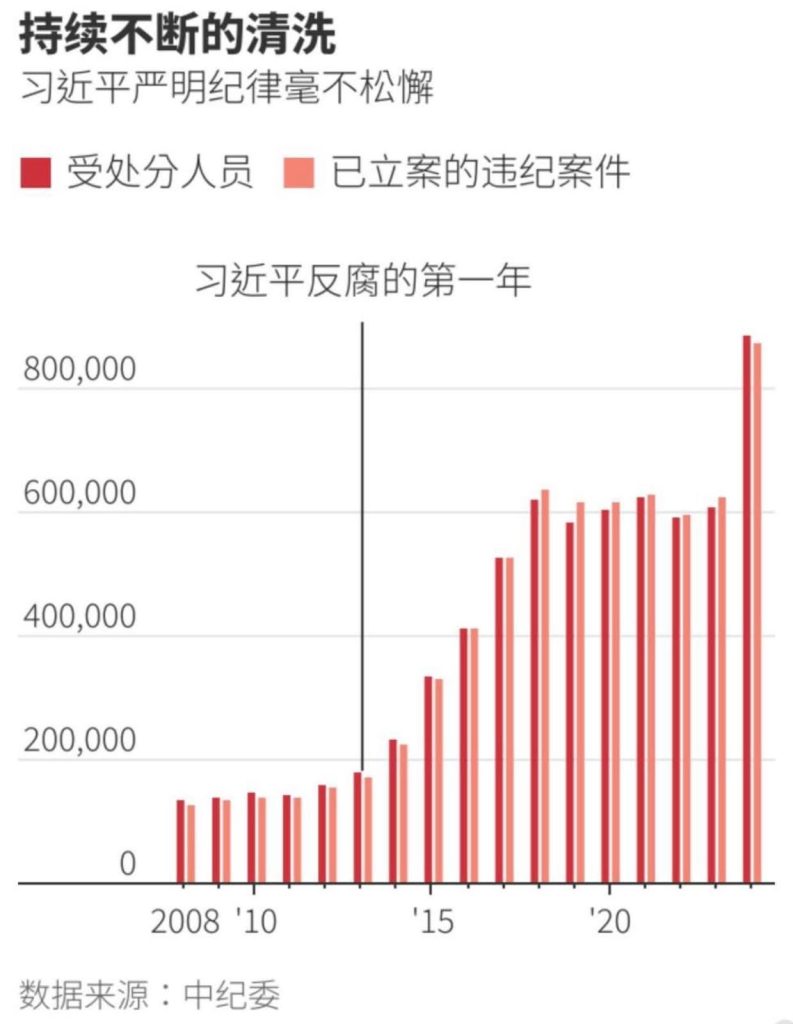

According to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection’s ( 中纪委)website, over 870,000 disciplinary cases were filed nationwide in 2024, a sharp increase compared to the annual average of over 600,000 in the previous five years.

Ongoing rectification campaign, Xi Jinping’s unrelenting strict, impartial discipline

Lighter bars: cases filed

Darker bars: punishments implemented

Note: 2013 is beginning of Xi Jinping’s first anti-corruption campaign

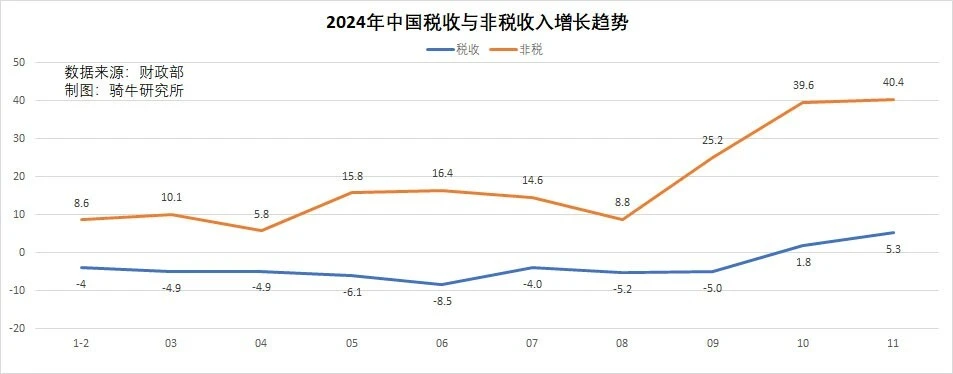

Confiscation and penalty-based revenues have obviously increased. Data from November 2024 show that confiscation income reached 288.9 billion yuan, a year-on-year increase of 40.4%.

Blue line: Tax revenue;

Yellow line: Non-tax revenue

A country that chooses not to enable job creation or growth in consumption, but instead turns its own “knife” inward to openly seize the assets of a relatively small, wealthy group of its citizens as a way to save the economy, is doing something beyond comprehension. This terrifying economic model has destroyed countless individuals and families, and its purported “5% GDP growth” comes drenched in blood.

Jeanette Tong is a research fellow at Citizen Power Initiatives for China.