By Wei Zhou

Source: Tencent, May 20, 2024

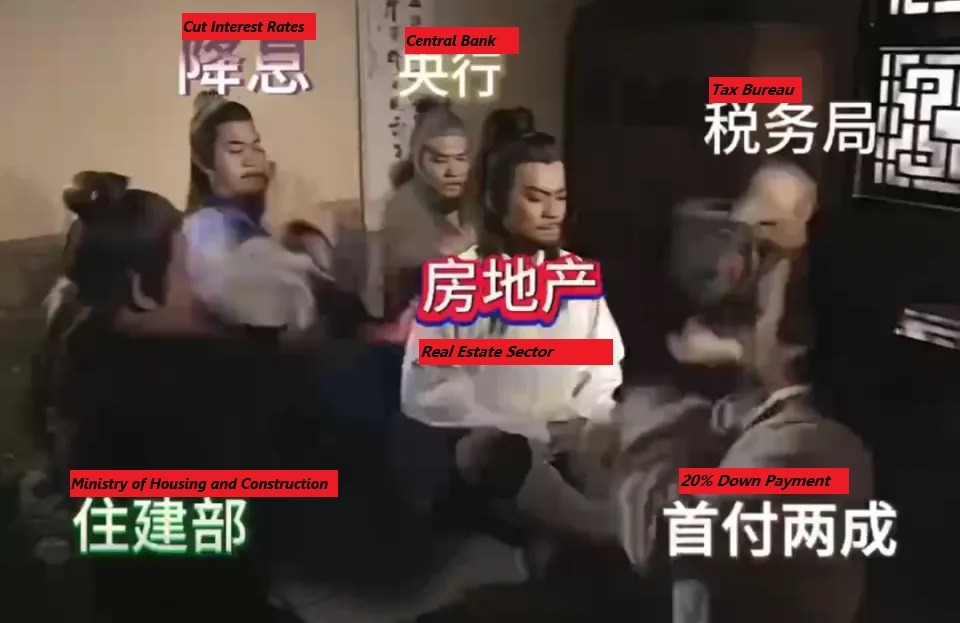

Netizens compare the current real estate market to a common scene in Chinese kung fu movies—many martial arts masters form a circle and channel their energy to the hero sitting in the middle to help him recover from his injuries. Similarly, the government is using measures like interest rate cuts, central bank support, tax incentives, and lowering down payments in hopes of saving China’s real estate market.

Readers must have noticed that the recent policy steps regarding the real-estate market have been unprecedented: the down payment for a first home can now be as little as 15%, the lower limit on mortgage-interest rates has been removed, and the personal provident-fund loan-interest rate has been reduced by 0.25 percentage points. But will this have any effect on the long-sluggish property market?

There are those who say that it already has. At least in Shenzhen, since the launch of the new policy on May 6, for some real-estate projects the number of inquiries has increased by 40% — “We are simply too busy on weekends, receiving more than a dozen groups of customers each day.” According to data from the Shenzhen Real Estate Agency Association, during the week of May 6-12, Shenzhen’s contract signings for existing homes were approximately 1,361 units, a month-on-month increase of 201.8%.

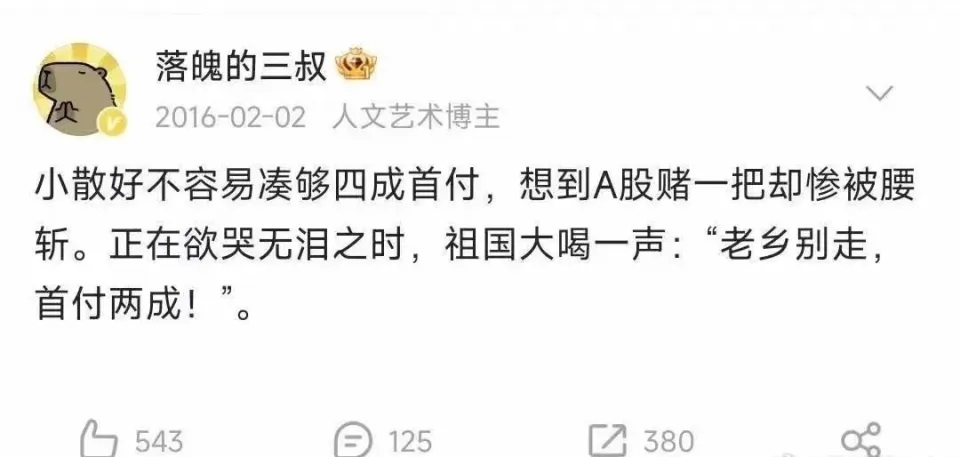

However, if you talk to people around you, you will find that most react very coldly to this. There are many jokes circulating on the Internet that this rescue measure is simply an attempt to use every possible way to get more money out of ordinary people’s pockets. Some people even pulled out a joke from eight years ago, which now seems like a prophecy.

Xiao San (ordinary people) finally managed to collect the necessary 40% down payment, but when he gambled it on A-shares, he lost half. Just when he is crying his eyes out, his motherland shouts loudly: “Don’t leave, my fellow countryman, please stay, and pay only 20% down!”

How to understand this contrast? I think the two things are actually not contradictory. Think about it: just like when the two-child policy was first relaxed, there was indeed a small rise in births. Some couples who originally wanted to have children but had been unable to do so quickly took this opportunity to catch the last train. However, this was unsustainable, because on the whole society as a whole has a long-established desire to have fewer children.

The current measures to save the market, whether in the form of reducing down payments or cutting interest rates, can really only affect those who wanted to buy a house anyway but had been deterred before by constraints. Originally, they had to save for another two years before they could buy one. Now that the threshold has been lowered, they can enter the market immediately. In other words, this move to stimulate the market is actually coming at the expense of the future.

Not only that, lower down-payment ratios and lower mortgage-interest rates mean that the risks faced by banks and other financial institutions have increased. Because the conditions for home buyers have been relaxed, the probability of default will of course go up. However, compared with the short-term pain caused by current houses being unable to sell, this future pain be will be enduring.

Relaxing the qualifications for buying a house does not mean lowering the housing price — the house is still so expensive, and those who couldn’t afford it still can’t. At most, lowering the down payment will only allow you to buy it now, without having to wait another two years, as if the government were lowering its noble self to be in your service. Well yes, the down payment of 2 million has dropped from 40% to 20%, but the amount to be repaid has also increased from 60% to 80%. You won’t be paying a penny less.

Of course, having said that, if house prices plummet, the impact will be unbearable: buyers who bought at the top will be full of resentment, while the remaining potential buyers may still choose to wait and see, hoping for an even lower price. By then, the situation will become even more embarrassing. Before, although it was difficult to get off the bull, at least it was possible to find a way to dismount slowly.

Here’s the problem: This seems to be an expansionary move, but not only does it come too late, it is still far from enough for a large number of people who want to own their own homes. This in turn means that as a rescue move things are stretched too thin, and the government doesn’t have much left in its toolbox — regulators can’t just order real-estate companies to cut prices.

It is undeniable that the current housing prices in many cities are still unaffordable for ordinary people. In the bubble-economy period when people lost their minds, they flocked to homes as if the market were merely like the one for cabbage, but buying actually depends on an expectation that the price of the house will keep increasing, so if you buy it now, you will make money, which is more cost-effective than any other investment. However, this expectation has now been shattered.

Once market expectations are broken, it is difficult to turn them around. When people no longer believe that housing prices will continue to rise, homes will no longer be an investment option or even a means of preserving value. After all, the current general market expectation is that housing prices will be on a downward trend for the next few years. The so-called idea of buying when the price rises and selling when it falls, well if you don’t have an urgent need, or find yourself with too much money, why should you rush to buy a house now? On the other hand, if you are not able to sell now because of market conditions, why be so eager to rush into the market?

This general mentality of wait-and-see and even outright bearishness means that it is impossible for the property market to regain its past glories. The various current rescue measures, regardless of the specific modalities, are essentially to extend the life of the old model as long as possible to avoid a hard landing. However, this will not allow the development of a new model.

If such a transition could occur, if houses could not be sold, at first glance it might appear that the market is weak and all parties are in trouble. But this is the just the inevitable pain of this transition. If you know that the old model is unsustainable, then even if shock therapy is too violent, thus undesirable, you can at least open your imagination and think about what the new model will look like, right?

2021: You will increase the price! You will borrow! You will acquire land!

2022: My dearest, will you please buy land? Will you please borrow? You know I love you.

Under the original land-finance model making money was easy. But there was a major drawback, which was that the wealth of countless Chinese people became “dead money.” How many families emptied every wallet in the family just to save money to buy a few cement houses to live in? This inevitably reduced what people could spend on other things, not to mention investing in other things — real estate itself became regarded as the largest investment for ordinary families.

In ancient agricultural societies, people’s first reaction when they got rich was to buy land, or turn their money into gold and silver and bury it underground. No matter which one it was, the result was that the money no longer entered circulation, and thus became “dead money.” In early modern Holland, many businessmen chose to buy land after they became prosperous. Adventurers became land aristocrats, and suddenly the golden age of the Netherlands was over. Real estate is actually equivalent to land, gold and silver in ancient times, its popularity making it difficult for large amounts of money to circulate — think about it, real estate is called [using another common Chinese term for it] “immobile wealth.”

The secret of the modern economy is precisely to keep capital flowing and to continuously invest it in new frontiers. If a society obviously has capital, but it is difficult to “make money from money,” then it is very conceivable that it is quite backward in finance and cannot afford much in the way of consumption. Lacking these, it will be difficult to expand the economy.

At present, the younger generation has figured out that since houses are so expensive, they may not be able to afford one even if they work all their lives. And if they buy one, the price may drop, so why bother? It’s better to be happy enjoying the flowers you deserve. As long as you abandon the burden of a house and thus don’t have to pay off the mortgage, your life will suddenly feel much easier, and every month you will get thousands extra to spend out of thin air.

Both Japan and South Korea have experienced this. Since the bursting of their bubble economies, the younger generation generally has no interest in buying a house. Especially in Japan, the property taxes required to buy and live in a house are as high as 5% of the home’s price. If the house were hypothetically sold, the property tax that must be paid, the transfer tax (39%, 20% for homes over 5 years old) and the capital-gains tax now would combine to greatly discourage young people from buying. When there is uneasiness about the future, purchasing large items will only increase the burden on one’s shoulders, which is bound to deter some.

At first glance, this may seem like a weakening of the property market, but in fact, it is precisely because of this that the real estate bubble can gradually deflate, and the market mechanism can play a role, allowing housing prices to gradually return to normal. At the same time, when people no longer spend their money so enthusiastically on buying houses, but instead on improving their own lives, the originally squeezed consumer-goods market will slowly recover.

Judging from the precedent of Japan, after the bubble burst, although the country experienced a long period of economic weakness and seemed to fall into the state of being a low-demand society, the market gradually returned to rationality, and people’s quality of life actually improved. Of course, China may not be the same as Japan (perhaps we should be so lucky), but at least we need to be clear: the old model is not worth any nostalgia, and the new model is not necessarily a bad thing.

Of course, I don’t know what things will be like in ten or twenty years, but I think one thing is certain: it will depend on the choices of millions of ordinary people.

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/?p=247842&preview=true before the text when reposting.

The author’s point of view does not necessarily represent that of this journal.