By: Jeanette Tong and Evan Osborne

On Jan. 19, British pianist Brendan Kavanagh encountered several Chinese tourists at London’s St Pancras station while live-streaming his piano performance, something he does routinely. These individuals, holding the Chinese flag, expressed discomfort with Kavanagh’s filming them. They asserted, rather remarkably, that such was not allowed under Chinese law, and accused Kavanagh of racism for referring to their flag as a “communist flag.” In response, Kavanagh emphasized the freedoms allowed in Britain, noting that while in the United Kingdom, he’s subject to British law, not Chinese law.

The video gained widespread attention, accumulating more than 6 million views. As public discussion intensified, the reported identities of the individuals were revealed as a Chinese-language teacher said to be associated with Confucius Institutes in the U.K., and a woman who reportedly has hosted events for the Chinese embassy in the U.K.

Some have speculated that these two may have been conducting “public relations” activities for the Chinese United Front Work Department on the day of the altercation, and if that’s true it could partly explain their reluctance to be captured on video.

Another woman who was there, Liu Mengying, released a video to explain the incident from her perspective. She claimed that Kavanagh touched her friend’s hand while she was holding the flag and that, as Chinese nationals, they felt responsible for protecting it. She also mentioned Kavanagh’s comment about the flag, calling the word “communist” impolite.

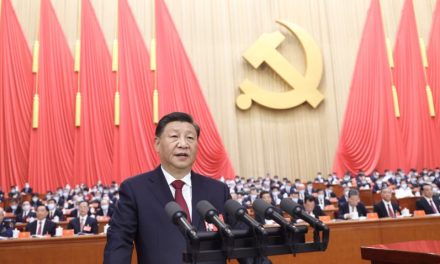

This incident highlights apparent confusion among some Chinese nationalists. The accusation of racism indicates hypersensitivity about a reference to communism, likely the byproduct of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) long-standing effort to integrate party and state. The reaction suggests a complex understanding of patriotism and party loyalty in China, where the party and the state are inseparable — the party is the country, and vice versa.

This concept, different from the way that people think in democratic nations, is explicitly delineated in the CCP’s “Outline for Patriotic Education in the New Era,” which states that the People’s Republic of China is a socialist state led by the Communist Party. The fate of the motherland is intertwined with the destiny of the party and socialism. From an early age, Chinese are taught to love their country and the party equally. And today’s Chinese nationalists, passionate about their party-cum-country, may react vehemently when others refer to the party’s name. Could this be because they understand the havoc that communism has wrought worldwide, and know that it is notorious in the West?

The incident also reflects patterns of behavior by members of the CCP’s United Front Work Department overseas. The agency, responsible for influence operations, skillfully exploits race for strategic advantage. Any voices or actions unfavorable to China are labeled not as “anti-comunist” or things done in defense of the rights of the Chinese people, but as racial discrimination, in an attempt to silence them. This accusation can evoke sympathy and a protective instinct from many in the general public — since most people who hold universal values would say they oppose racism — and shift attention away from any accountability. We saw this in the reaction of the U.K. police officer who whispered to Kavanagh, “You can’t do that,” when he appeared to be simply standing up for himself.

Additionally, drawing upon race/ethnicity can help the CCP to manipulate nationalist sentiments to control both its domestic population and the overseas diaspora. By emphasizing or exaggerating reports of racial-discrimination incidents in Western countries — where many Chinese choose to live despite the supposed ubiquity of racism — the CCP can instill fear and worry among individuals about potential discrimination outside China. This promotes a psychological “belonging” to the CCP collective.

If those involved in the incident were indeed among China’s “wolf warriors,” their impromptu expressions reveal the typical habit of using authoritarian party-state discourse. When the pianist stated that he had no obligation to obey Chinese law, a man loudly leveled accusations at Kavanagh, such as “Don’t touch her,” implying that he had, and demanded: “Who are you?” Such aggressive behavior highlights the difficulty many CCP-conditioned people can face in communicating with people from other cultures. The party’s domineering approach generates communication barriers and sometimes outright hostility. The Chinese government not only fails to correct this, but benefits from fueling these reactions in the media.

In recent years, Western democracies have tried to constrain the CCP’s disruptive tactics, but the free world seems to remain largely unprepared for China’s United Front wolf warriors. They continue to wreak havoc on society, with a goal of disrupting order and prosperity. Liu Jianchao, minister of the CCP’s International Liaison Department, recently stated that China does not seek to change the current international order. However, there is evidence that the CCP openly does so, such as by:

-

Discrediting the voting system of the United Nations;

-

Influencing the internal affairs of countries in the Global South;

-

Infiltrating international organizations and changing rules;

-

Using economic coercion worldwide; and

-

Seeking to repress people (including by telling a Brit in London to abide by Chinese law).

Therefore, does anything that a Chinese government official says really merit our trust?

How should we respond to these wolf warriors who would disrupt social order in the West? One answer is to show them images they dislike or fear: Winnie the Pooh, banned in China after memes compared Pooh to Chinese President Xi Jinping; the Tank Man of Tiananmen Square; or the flags of Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet and Xinjiang — all things that may remind them that their true identity is not communist but Chinese. If they have been recording an incident, they will stop immediately because any censored image — and the CCP has a long list of censorable content — appearing in their video or photo will be silenced by Big Brother. This technique has had some success worldwide.

The struggle between champions of democracy and freedom and the totalitarian Chinese Communist Party, with its culturally ignorant loyalists, is becoming increasingly surreal. It’s a situation to which we must draw attention and learn to better respond.

Jeanette Tong is a research fellow at Citizen Power Initiatives for China.

Evan Osborne, Ph.D., is a professor of economics at Wright State University and the author of “Reasonably Simple Economics: Why the World Works the Way it Does” and “The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement: Corporations and the People Who Hate Them.”