By Evan Osborne

The Chinese government has recently substantially increased its scrutiny of previously welcomed foreign businesses. The Wall Street Journal recently reported law-enforcement interrogation of employees at numerous Western companies, as well as the disappearance of the Japanese businessman Hiroshi Nishiyama into the bowels of the Chinese criminal-punishment system on what was supposed to be his last day in the country. As foreign businesses consider the implications of the new policies it may help to consider a previous outburst of such sentiment, since what once was can provide clues about what might soon be. The accounts that follow are based on several sources: testimony from the historian Jung Chang, one of the first Chinese to be permitted to study abroad after the Communist Party of China (CCP) takeover; Robert Koh, sent by his father to study in the U.S. before 1949 and someone who returned after the CCP victory to build the new China; and a 1979 account by Thomas N. Thompson, China’s Nationalization of Foreign Firms: The Politics of Hostage Capitalism, 1949-57

The current campaign already recalls to some extent one launched in the wake of the Chinese Communist Party’s triumph in 1949. Before the Japanese invasion of first Manchuria and the. the rest of China in the 1930s, much of the country had been substantially remade since the country’s forced opening in 1842 through the efforts of both both domestic and foreign businesses. While Shanghai after 1842 became known for vice, crime and corruption to some, it also had for decades attracted huge numbers of migrants from the rest of the country, who often found great success in an unprecedentedly free environment, remaking the way China did business and putting a Chinese touch not just on Western business models but Western cultural forms such as the novel and movies. (Their descendants now often take great pride in being native Shanghainese, since 1949 a difficult city to get CCP permission to live in.) While after 1842 Shanghai was among many Chinese cities that had had districts where Chinese governments had no sovereignty, these were all returned by the Allied governments to China during World War II (while the territories were occupied by Japan) as a gesture of solidarity.

After 1949, the communists sought to remake the economy, motivated by a mix of Marxist theory and the standard desire for vengeance that festers during civil wars. Agricultural collectivization in the early 1950s was notably violent, as CCP functionaries first swept throughout the land and imposed a brutal, seemingly random retribution campaign against accused landlords and “rightists.” In the anti-landlord campaign of 1949-1953 in particular, peasants were initially given land taken from landlords (although the two parties sometimes secretly agreed to restore the old arrangements). Ultimately, the peasants were moved, in several steps, into larger farms more directly controlled by the CCP, culminating in the large communes that helped lead to the catastrophic famine of the late 1950s.

In the cities, the takeover of private business was somewhat more subdued. The defeated Kuomintang (KMT) after the Japanese surrender had seized many Japanese businesses, and the victorious CCP government quickly seized them from the KMT in turn, along with all private schools and universities and all newspapers. But some private, Chinese-owned businesses were classified as “national capitalists.” These had owners who had at a minimum not supported the KMT during the civil war, and sometimes supported regime change. Also prominent among this group were business owners who had fled in the chaotic years before 1949, only to return to help rebuild the country after the CCP victory.

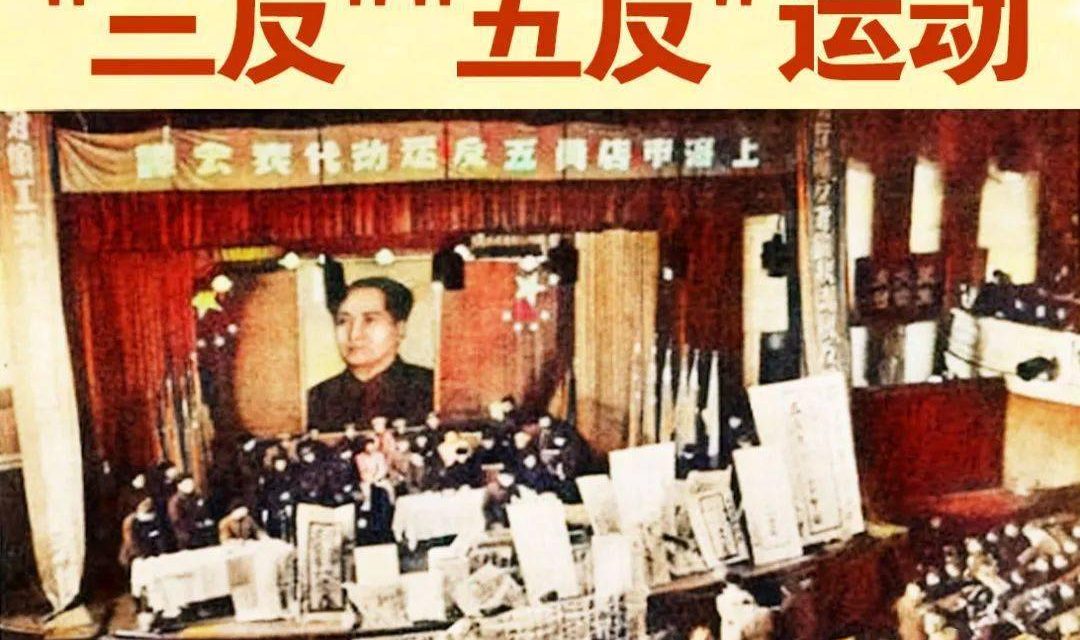

And the theoretical role for these national capitalists was to share their expertise during the transition to communism. Alas, of those who remained in their firms, many of them were quickly forced to undergo the notorious “struggle sessions,” in which those seen as exploited by the “capitalists” confronted them, with the purpose of getting them to confess their class sins. (Some “capitalists” were, along with many other victims, sent to labor camps.) As backdrop, CCP authorities announced that capitalists would be among the targets of the “three resists” (三反) and then the “five resists” (五反) campaigns in late 1951 and early 1952 respectively. In addition, while the party for a time let some retain nominal title to their businesses, a growing web of restrictions on the prices they could charge to now-exclusively state buyers, the wages they had to pay, and the number of CCP functionaries they had to hire in management and other roles combined to make their lives increasingly miserable; it has been estimated that hundreds committed suicide in Shanghai alone before the nationalization process was completed.

And with remarkable suddenness, completed it was in late 1955. Their will having been broken by several years of growing control over their businesses amid national campaigns targeting them, the remaining Chinese business leaders in Shanghai were summoned to a meeting with Mao Zedong himself. Mao, despite the horrors he inflicted on the Chinese people starting in the late 1920s, up close and personal was capable of great charm. And so he asked the assembled businessmen if they wished to accelerate the transition to communism by having the state take over their businesses then and there. Overwhelmingly, they said they did, and after several days of celebratory parades, the task was accomplished in the once-great commercial dynamo within days, as around the country.

This left, particularly in Shanghai, only the foreign-owned businesses. They had been operating in Shanghai since the Treaty of Nanjing ending the First Opium War. The treaty had changed Shanghai from a medium-sized city of about 250,000 people with a good location just south of the Yangtze River delta but not a center for taking the imperial exams (long a source of economic development) to a sprawling, vibrant metropolis with a population of many millions. In the immediate months after the CCP takeover of Shanghai in May, 1949 and the announcement of the establishment of the People’s Republic in Beijing in October, many foreign businesses felt there were opportunities to cooperate with the new government. Indeed, the CCP had already requested of the foreign business community in both Tianjin and Shanghai that they remain, which they did. The CCP also reached out to newfound exiles in Hong Kong asking them to return, which also contributed to this modest optimism.

But the CCP’s Marxist absolutism was a fatal blow to such hopes. To Mao and the other CCP leadership foreign capitalists, unlike the domestic ones, were double exploiters. Their captive proletariat were thought to have worked at subsistence wages (even though jobs at these firms had long been desired by Chinese, because the pay was significantly higher than what they could get from Chinese employers), and as the CCP saw things much of the resulting Marxist surplus was repatriated overseas, so that the Chinese got nothing. Rather than Maoist sweet-talk, the campaign to take over the foreign-owned means of production relied from the start on intimidation, and as the campaign went on the degree of intimidation increased. That many foreign-owned firms had once again become quite profitable after 1945 did not help.

In addition, the campaign against foreign firms was conducted mostly after Mao’s decision, once he had received Stalin’s consent and pledge of military support, to enter the Korean War in October, 1950. The U.S. and British governments soon began seizing Chinese assets of potential military use, particularly in Hong Kong. As a result of Chinese entry into the war, the United Nations imposed a boycott of the PRC, although (unlike North Korea) not a blockade.

During this time foreign firms first faced the same rules imposed in 1950 as domestic firms — rules on wages and prices and insertion of CCP officials into company management most prominently. But another restriction affected only foreign owners, who were now required to obtain exit visas to leave the country. Their firms were not technically confiscated, yet for all finance matters they were soon required them to work exclusively with the new state banking institutions, which in combination with CCP control of most firm decisions made them de facto CCP property. In the wake of the “five antis” anti-capitalist campaign, by the middle of 1952 foreign firms that had originally planned to stay were making plans to leave China.

Scholars have termed this period “hostage capitalism,” and it got worse. Diplomatic entreaties by the British government had been begun in April 1952, but the CCP, seeing the very presence of British firms as illegitimate exploitation, was uncompromising. Having decided it would be too diplomatically dangerous to subject foreign businessmen to the struggle sessions that local owners had endured, the CCP nonetheless subjected them to “liquidation fees,” and their managers, while still doing their jobs, were often subject to house arrest, in addition to being prohibited from leaving the country. At the same time, CCP officials imposed a lengthy legalistic process on foreign firms in which, before closure could be discussed, the CCP had to discuss among themselves whether they were even eligible to close. All of this was done with the firms themselves having no say in the matter.

By January 1953 the goal of foreign firms became simply to get out as cheaply as possible. In addition, CCP regulations meant that many of their operations were losing money, and to keep them afloat the parent firms had to send money to their Chinese subsidiaries. By 1954, the parent corporations had decided to stop doing so, since much of it was simply being confiscated by the CCP. But the mandatory paying of “fees” (protection money in a sense) to the CCP continued. By the time of Mao’s (equally extortionary) accepted offer to take over domestic businesses, most foreign firms had agreed to transfer the companies, and any infrastructure or other assets, to the CCP while paying extensive liquidation fees. Many firms owned by the foreign firms were argued to be illegitimate, hence meriting a heavy discounted calculation of their value, because they had been entangled with Japanese or KMT entities at some point. The Chinese government sometimes also demanded transfer of technological knowledge. Any early promises of amicable cooperation in the interest of the Chinese people had by this time long been revealed to be hollow. The coerced sales were largely completed by the summer of 1954, and most of the remaining foreign employees were released and allowed to leave, although the last remaining firm, the textile firm Patons and Baldwins, was not allowed to exit until 1957.

Similar promises are made to foreign companies now by the CCP — on opportunities to make and keep profits in China, on the protection of intellectual property, on the normalization of business law, and on other things. But such sweet talk has been heard before. And so in today’s China, as in 1949’s, businesspeople, especially foreign businesspeople, should be aware that things can change quickly, simply because in the past they have.

Under Xi Jinping, Western businesspeople are seen once again as a threat to CCP power, and thus in his view ultimately as an enemy of the Chinese people. If the past is any guide, if things continue to deteriorate foreigners’ commercial and even personal liberty is at growing risk. When thinking about their presence in China executives should remember that they are not there to make their own and their Chinese customers, investors and employees better off. They are there merely at the sufferance of, and to do the bidding of, the CCP.

Evan Osborne is Professor of Economics at Wright State University and the author of Reasonably Simple Economics: Why the World Works the Way it Does (2013) and The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement: Corporations and the People Who Hate Them (2007).