This piece is translated by Yan Li, Evan Osborne, and Alina Wang.

Note: Who are those arrested for participation in China’s white-paper movement? While some of their names have appeared in English-language media, very little has been reported about them as individuals. But they are individuals — with their own individual dreams, individual fears, individual lives. To try to partly remedy this deficiency, we have translated this report from Yibao Chinese, which was published on February 8, 2023.

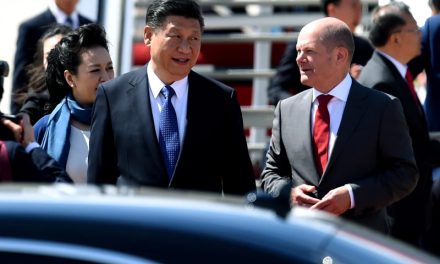

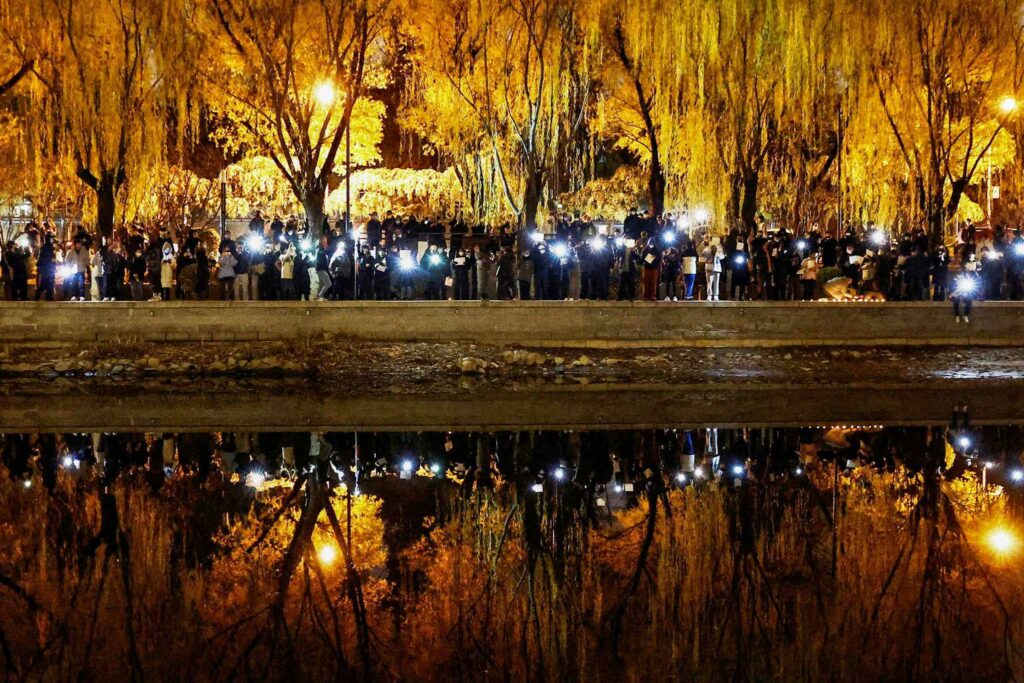

November 27, 2022 (Beijing): A woman holds a piece of paper containing the date of the Urumqi fire disaster, to commemorate the dead. Photo: Thomas Peter, Reuters/Shutterstock

This article is jointly published by Duan Media and the NGOCN Voice Project, and was first published on Duan Media. This article is also NGOCN’s second in-depth report on those in the White Paper Movement, who were arrested, the first being “Arrested: Those Youths” (《被捕者:那些青年》.

On the afternoon of January 20, 2023, the day before the Lunar New Year, and after losing her freedom 29 days before, 27-year-old Cao Zhixin saw her lawyer for the first time,

This was the meeting room of the Chaoyang District Detention Center in Beijing. Cao Zhixin was wearing a khaki cotton jacket and gray cotton trousers, which were the standard “uniform” of the detention center. As usual, the meeting was limited to 40 minutes.

“She is very strong,” one source said.

The night before that, in particular on January 19 after 11 in the evening in Beijing, several who had participated in the “Liangmahe Memorial Activity” and then were detained in the Chaoyang District Detention Center were released on bail one by one. There were reporters Yang Liu, Qin Ziyi and others, but Cao Zhixin was not among them. She and several other close friends of her age, including Li Yuanjing, Zhai Dengrui, and Li Siqi had been announced as arrested at the same time. Their crime had been changed from the previous “gathering together to disturb order in a public places” to “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”

According to people familiar with the matter, at least 20 people were authorized to be arrested that night, all in relation to the mourning and protest that had taken place at Liangma Bridge in Beijing on the night of November 27, 2022 against the continuing epidemic lockdown.

Insiders also said that Cao Zhixin was crushed when she learned that she had been arrested. She really never thought that participating in a normal mourning event would lead to such serious consequences. Each time she received greetings and good wishes from her family and her boyfriend, she couldn’t help but cry.

Before meeting the lawyer on this occasion, she didn’t know that the video she recorded before being arrested appealing for help had spread all over the world. In that video, she had a premonition that she was going to be “disappeared,” and pointedly asked, “We young people just mourn our fellow citizens normally. Why should we pay this price? Who are we who must bear this responsibility?”

By January 9, her lawyer had already applied for bail for her, but the application was denied. On January 17, the lawyer submitted a “Notice of Approval of Arrest” to the prosecutor, arguing that she had only “participated in spontaneous public mourning activities, which did not constitute a crime.” But this statement was rejected by the prosecutor.

Another young woman, 27-year-old Zhai Dengrui, who was arrested on the same day as Cao Zhixin, did not even see her lawyer before the Lunar New Year, cumbersome application procedures and constant “mishaps” having made the meeting very difficult to arrange.

Before losing her freedom, Zhai Dengrui was preparing to apply to the University of Oslo in Norway to study drama as a graduate student. Ms. Zhai, who loves literature and drama, had been preparing for this for a long time. After her arrest, her family wanted to ask for her application password during the meeting with the lawyer so they could submit the application for her, but because the lawyer was unable to meet with her for such a long time, the application deadline was missed, and they could only convey their regrets to her.

There was also Li Yuanjing, who had graduated from China’s Nankai University and then returned to China after studying in Australia. She is a professional accountant and “the richest” among the arrested. And Li Siqi, a young woman who loves writing and reading and calls himself a young “non-freelance writer.” The Goldsmith College at the University of London, from where she had graduated, issued a statement of support for her on January 28, 2023.

These were four close friends of the same age. Before they lost their freedom, they all lived among the hutongs [a traditional small lane, common in parts of Beijing]

in Gulou, Beijing’s old city. They all had a distinctive temperament characteristic of literary-minded youth: they loved reading, writing, film screenings, and underground music. They were keen to explore niches in the city that have something of a rebellious temperament.

They care about social issues, but they had not yet had a chance to make a real public statement. In the eyes of one of them, Cao Zhixin, and her friends, they are merely “semi-activists,” a group of young people who love life. “We are interested in everything and are willing to try anything.” But there is still a certain distance between them and genuine activists.

They all went to college around 2015. Since then, China’s weak civil society has been continually suppressed. In the last decade, many conversations and actions once common in the public square have been hard to find in Beijing. However, in a city once rich in literary and artistic resources, Cao and her friends had flourished in the remaining crannies and had developed their own path to follow. They bear the unique mark of this generation.

“They are a group of people with the capacity to reflect. They are also activists.” says another friend of Cao Zhixin and Zhai Dengrui, A Tian. (A pseudonym is used here.) A Tian left Beijing in September 2022 to pursue her doctorate. She said she would have been with them that night if she had been in Beijing.

“It was going to happen sooner or later, and these three years of extremely repressive epidemic control are only one reason. In this land, as long as injustice is present, resistance is bound to happen,” A Tian said.

“They can take it for a long time. But now, with them facing harsh sentences for just one street protest, it seems like the beginning of the end,” A Tian said. As a friend, she ached for them.

November 27, 2022: street signs for Urumqi Road were taken down in Shanghai, after people had gathered there for days to memorialize the victims of the Urumqi fire. Online photo.

1. Arrested

December 18, 2022: On the day of the World Cup final in Qatar, Cao Zhixin arrived in Beijing from Shanghai.

More than twenty days earlier, on the evening off November 27, after she and several friends saw information about a memorial service for the victims of the Urumqi fire, they all went to the Liangma Bridge not far from their homes. “To her, this was a natural thing to do,” her boyfriend later said,

She brought a bouquet of flowers and wrote down some poetry. Some in two of her WeChat friends’ circles saw photos she had posted there of her at the service. The photos merely showed flowers, poems, and young people standing together.

It already was late at night, and after leaving the scene she and her friends went to a bar near the Drum Tower to have a drink, and then returned home in the early morning. Her good friend Zhai Dengrui stayed with her overnight. She slept until dawn, and at this time, her anxious boyfriend, who was studying abroad, managed to reach her.

At around 11 AM, perhaps noon, on November 29, Cao Zhixin and her boyfriend were talking on the phone. On the other end of the phone, the boyfriend heard a cacophony of voices. It was the police coming to Cao’s room.

“She was a woman with a big heart. She often didn’t even lock her door,” another friend said later. Five or six policemen went directly to her room, located in a courtyard in a hutong.

She was taken to the nearby Jiaodaokou Police Station. According to Chinese law, a summons or subpoena should not lead to confinement exceeding 24 hours. Like most of the people who were taken away that day, Cao Zhixin was released and allowed to return home early the next morning, but had to leave her mobile phone, computer and iPad at the police station.

After returning home Cao Zhixin was a little worried, but she continued to live a normal life. On December 7, 10 days after the Liangma Bridge memorial event, the Chinese government announced the “Ten New Measures,” fully ending its earlier anti-Covid policies. Almost everyone around Cao was infected, and Cao was not spared either.

The government had suddenly ended all COVID-related controls. All over China, people unable to buy essential medicines now had no alternative but to try to save themselves. “People have finally gained the right to be sick with COVID at home,” writer Di Ma commented.

Yet it was in this atmosphere that Cao Zhixin and her friends became a bit more optimistic. Whatever happened, the government’s loosening of controls was actually an indirect admission of the failure of its zero-COVID policy, which seemed to vindicate the public mourning and protests.

Before the second time she was taken away by police, Cao Zhixin talked about what might happen with her friends.

One of her friends later indicated, “We thought at the time that there was a 50% chance that this matter would come to nothing, because everyone had just been expressing their grief in a normal way. There was also a 40% possibility that the people who were there would face several days of administrative detention. And there was only a 10% chance that there would be serious consequences,”

But in the end, contrary to their expectations, that worst outcome was what happened.

The World Cup final in Qatar on December 18 was broadcast live in the middle of the night in China. Cao Zhixin specifically bought fried chicken and arranged with her boyfriend to watch the final together. About halfway through the game, she suddenly told her boyfriend that she felt cold all over, because she learned that several friends who had been at the Liangma Bridge had been arrested again, including Yang Liu.

“Late that night, on the one hand there were cheers at the World Cup, Messi’s joy of victory, but on the other our hearts were crushed,” Cao’s boyfriend said. It was a strange night that he will never forget, with anger and anxiety intertwined in his heart.

The next day, Cao Zhixin took a train back to her home in Hengyang, Hunan. “She felt that even if she was arrested, she would still be with her family,” the friend said.

During five days in her hometown, Cao Zhixin quietly recorded a video. If she were to be arrested, this video would be released by her friends publicly. In the video, she wears blue clothes and has medium-length hair. She is a beautiful women with bright eyes.

On December 23, it was close to noon. Five or six police officers from Beijing knocked on the door of her home in Hengyang, Hunan province, and took Cao Zhixin away.

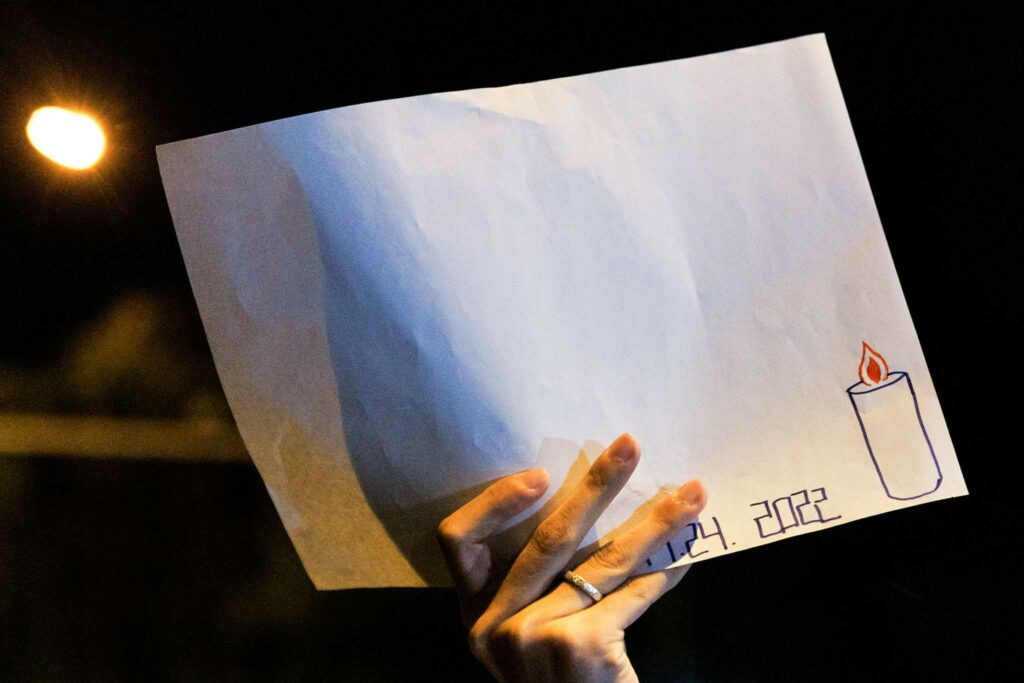

November 22, 2022 (Beijing): People gather for a vigil and hold sheets of white paper in protest during an event for the victims of the Urumqi fire in Beijing, Nov. 27, 2022. Photo by Thomas Peter/Reuters/Shutterstock Images

2. The Gulou Hipsters in their hutongs.

Cao Zhixin was brought back to Beijing by the police and was first detained at the Pinggu District Detention Center and then transferred to the Chaoyang Detention Center on January 4, 2023.

Soon after, a phone call from Cai Zhixin’s Beijing landlord reached her family in Hengyang, informing them that the lease would be terminated and that Cao Zhixin should move out from the apartment. On a cold January day in Beijing, her family had to entrust her friends to move her books and personal belongings out of her Beijing apartment at No. 1 Dongwang Hutong.

Having come from Hunan to Beijing to go to school and then later continuing to live there, Cao Zhixin has a kind of passion for hutongs. After leaving school, she had been renting a place in an alley near Beijing’s Drum Tower. Before she was arrested, she had been renting a one-bedroom apartment in one of the hutongs, in a small courtyard with a gate.

A friend said that the first house she rented in a hutong was even smaller, an attic made of corrugated metal. “When I was there, there were places where I couldn’t even stand erect.”

In July of 2021, Cao Zhixin finished the graduate program in environmental history in Renmin University of China’s history department. The topic of her graduate thesis was the city of Changsha during the late Qing Dynasty. She was fascinated by the history of the city and read Jane Jacobs’ classic book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” She liked studying cities’ texture and life.

“I’m from Beijing, but I don’t like hutongs. The environment in the alleys is messy and there are no toilets, which is unbearable for most people,” a friend said. “I don’t love Beijing like she does, but she and her friends who were arrested at that time loved Beijing’s multiculturalism, its folk ecology, and experiencing ordinary people’s lives there.”

“This time, they arrested young people who loved Beijing the most,” this friend recounted.

After Cao Zhixin graduated, her boyfriend wanted to go abroad to continue his studies, but she wanted to start her career. She had always wanted to work in publishing, and was able to work at several famous publishers before graduation, including Guangxi Normal University Publishing House and the Zhonghua Book Company.

As her boyfriend saw it, she wanted to work in publishing because she loved both to read and to write. In addition, having majored in history, it would be difficult to find other jobs anyway. Besides, the things other students were going to do, for example working in the civil service, at a state-owned enterprise, at a factory, in the propaganda service or as a junior-high teacher did not appeal to her.

But they all knew that in today’s China the publishing industry is actually “being suffocated.” Many publishing houses are facing financial crisis. And it is not easy for young people to gain a foothold in Beijing.

In the end, after a highly regarded internship, she stayed at Peking University Press as a full-time employee. She also works very hard. Today, on [the Chinese video-sharing website] Bilibili, there is a long video of her introducing the book “Global History.” At the time she made it, she had just arrived at the press and was getting up to speed on the ongoing promotion of this book.

“She is very smart, and the teachers admire her very much. She has scholarly abilities and is a sharp thinker. I always hoped that she could continue her studies overseas,” her boyfriend said. In fact, many of her friends have the experience of studying abroad, and she also wanted to go abroad and give it a try.

Her parents in Hengyang work inside the system, and most of her family members are in fact civil servants. But in the end, with her enthusiasm for reading, her maturation, and the experiences she had along the way, this girl gradually grew into someone her family didn’t know.

In 2018, she met her future boyfriend, and they started dating in 2019. They met at a film screening and were both getting their master’s degrees in history. After graduating in 2021, he went abroad, and the two continued their relationship across this new vast distance, speaking to each other every day. Sometimes, the two of them merely turned their video cameras on as they went about their daily business, each doing their own things. She might play the ukulele and sing. Love is sweet, he thought, and assuming they would be able to reunite, they must consider the important matter of marriage.

January 27, 2022: at a demonstration in Shanghai, one person being taken into custody. Photo: Shutterstock.

3. “A semi-activist, an interesting person.”

In the eyes of those friends who know her best, Cao Zhixin is just an interesting young woman who loves to do fun things. She is not so politically active. “She’s so young. Just out of school, her life was just getting started, and she hadn’t yet had time to do anything.”

Like many people who went to the scene at Liangma Bridge that night, she had no experience in civic activism. “After the protests in Shanghai the day before, there was a very optimistic atmosphere in Beijing that day. Many people who went to the scene didn’t even wear masks,” a friend recalled.

As far as her boyfriend knows, she and her friends had never participated in political activities, let alone really protested against anything. Many of them had never even spoken out publicly, nor made any kind of public statement.

“But what an interesting person she is,” said the boyfriend. She and her friends once went out to busk together. She is not a professional singer, but she just thought it was fun, like a joke. Everyone was happy and lighthearted, a fun bunch of friends.”

Her boyfriend believes that Cao Zhixin and some of her friends who were arrested can be regarded as “semi-activists” at best. They do some things together, but normal things — film screenings, book-club discussions, etc. These screenings and discussions focus on issues such as women’s issues, the environment, family, etc., but not things that are absolutely forbidden to discuss in China.

And most of her friends are people she had met within the last year. All of them had just graduated within the last two years.

She has a friend named Cao Yuan [no relation], who was also a classmate at the National People’s University, studying sociology. While in school there, they went to a film festival. Cao Yuan said, “I later saw her several times here or there, on the street, on campus, at the entrance to the school cafeteria. I became familiar with her.”

Cao Yuan participated in the editing of a social-media site devoted to anthropological questions. Like all of us, she focuses on similar issues, from literature, art, film to feminism, ecology, nature, etc., including political freedom. On January 6, 2023, the police took her away.

Like Cao Zhixin, these friends of hers basically lived in or near one hutong or another. “Many refined young people enjoy living in such an alley, without a toilet, and surrounded by couriers and food-delivery workers. Ordinary people can’t accept that. But we were willing to live in this down-to-earth way,” Peng Peng (for protection of the interviewee, a pseudonym is used here) said.

Peng Peng is also their friend. She said: “Basically all my friends have this temperament. They are willing to push back in small ways in their lives.” This resistance is often based on their perception of gender-based inequities and other injustices that are plain to see.

Liangma Bridge, which became their focus around that time, was a place that young people liked to go to. The river there used to be seriously polluted, but it was transformed into a very pleasant city park in 2019. Moreover, this area is also in the embassy district, with diverse cultures, and food from all over the world — Middle Eastern cuisine, North African cuisine, Indian cuisine, etc., and attracted many curious young people.

However, the urban development, the changes in the city’s appearance, cannot hide the increasingly repressive political atmosphere of recent years. In recent years, China has made no secret of its severe crackdown on speech. Whether in the media or in the schools, various topics have gradually become taboo. After three years of epidemic control, the environment has become more and more dispiriting. A friend said that after every party, screening or other such activity, everyone would still talk together, but in fact everyone was now “quite confused.” “The opportunity to discuss things is now over, and I don’t know what to do.”

Sometimes, these young people would organize hikes, go for a walk in the countryside together. Cao Zhixin likes small animals and cares about the environment. She had been to Nanjing’s Hongshan Zoo with her boyfriend before. Not long before losing her freedom this time, she adopted a baby wild boar at the Red Mountain Zoo. Donate a few hundred yuan every year to “give more meals to the little wild boar.”

November 27, 2022 (Beijing): People gather for a vigil to commemorate the victims of the Urumqi fire, while holding up blank pieces of paper to protest the Chinese government’s anti-COVI policies. Thomas Peter/Reuters/Shutterstock Video

4. Pubs, underground music, the unmentionable cracks in social space

May 2018 marked the 50th anniversary of France’s “May Storm” 1968 youth movement.

On May 11, 706 Youth Space, a private space located near Wudaokou, Beijing, held a “Salute to the 1960s” reading. The space was located on the 20th floor of a residential building and had been converted into a small, cramped library. This was one of the events held in honor of May, 1968.

People read articles and poems. Someone attending wore a black T-shirt with white words written on it: “We wander in the darkness of night until the flames consume us.” This was the title of a documentary directed by Guy Debord.

Qin Ziyi (released on bail pending trial on January 19, 2023) was also at the “May Storm” commemorative event. She and some other attendees later became friends.

706 was a utopian, autonomous space initiated by several young people in 2012. Due to various problems encountered, it is no longer sustainable in today’s Beijing. Many people read, discussed, and even lived here. It is a place where many friends met and influenced each other. Zhai Dengrui and Li Siqi also met each other there and became friends.

At the beginning of this century the Internet was booming in China. After the development of the market economy in the 1990s, the spread of liberalism, and the awakening of citizens’ awareness of their rights, in Beijing, online and offline public spaces functioning as places for discussion kept popping up. Sanwei Bookstore and Wansheng Book Garden were all in their heyday. Back then, Beijing had a vibrant community life.

After 2012, when Pengpeng moved to Beijing to attend university, a “new era” commenced, many of these public spaces were suppressed, and things gradually became more bleak. But 706 Youth Space still existed and even put down roots in the crack it had found. During the period when Pengpeng and his friends often visited, “the young people in that space were very sensitive to various issues of inequality and injustice.”

Pengpeng in those times often went to the One-Way Street Bookstore, and the Halloween Book Garden, which had both been reduced in size. In addition, young people went to some taverns, some with underground music, micro publishers, and other such places. Cao Zhixin was this sort of person. She liked traditional folk songs, including New Pants [a Chinese rock band founded in 1996], the songs of Zhang Xuan, etc. “She also liked underground music, but she wasn’t the most intense sort of fan,” recalls her boyfriend.

Pengpeng also liked underground music. Looking back on the days when she got to know her friends, she would think of a tavern called “Pause” in the alley, although it no longer exists. It was less than 10 square meters in area, squeezed into the crowded alley, but through a glass window on the wall, one could see inside.

At 10 square meters, this may have been the smallest tavern in the world. But in the remembrance of some of these friends, it was a place frequented by “progressive youth.”

In 2018, when workers at Jasic [a maker of construction machinery; workers there were fired after trying to organize a union, which generated sympathy strikes elsewhere in Shenzhen] went on strike in Shenzhen, some students from Peking University went to the scene to support them. Many young people were affected by this event. In the eyes of observers who pay attention to young Chinese intellectuals, they were “left-wing youth.”

At one time, Pengpeng and her friends were also frequent visitors to Pause. She remembered those cold nights. The tavern was so small that sometimes everyone could only stand at the door. When it was cold in winter, everyone could still chat outside, and the tavern provided military-style coats.

There would often be “unplugged” performances in the tavern. A music group called Kaleidoscope used to improvise there on nights when the electricity was out. During the day, a music group performed via video on a rooftop in an alley. One winter afternoon, the sun was bright and dazzling, the wind was blowing, and the sky was blue. They played and sang until night fell, and wearing blankets because of the cold.

Once upon a time, the pubs in these out-of-the-mainstream areas of Beijing not only were filled with the artistic spirit of young people, but more importantly, provided a public space for them. They were there looking for like-minded companions, to find freedom in a country increasingly under surveillance.

These self-proclaimed “low-rent, amateurish” taverns attracted many musicians and artists, and young people followed them there. “Opening a tavern itself is not what we want to do most. As I said on the program, people must have a process to find themselves.” In many programs and articles, tavern owners once said things like this. “Our tavern seems to have a utopian temperament, and all the people we attract are good comrades.”

“I’ve been thinking about the meaning of opening a small bar in some Beijing hutong. In fact, opening a bar while young can help young people carry out a personal idealistic experiment. This is something that the current society cannot provide.” This may be seen as the spiritual vibe for these taverns.

In the experience of this circle of friends, there was more than one such small personality-laden tavern in Beijing. Another one, which opened for 2 months in 2019, sold 2019 glasses of wine and then decided to close.

In addition to these taverns, there were many music spaces in the area around the Drum Tower that Cao Zhixin and her friends liked. From Di’anmenwai Street in the west, Dongsi in the southeast, and in an area not exceeding the Lama Temple in the north was the core area of the second ring road. The area is less than 5 square kilometers and composed of several streets and countless small alleys. It was then the center in Beijing of small performance venues.

This little slice of Beijing, with music as (as it were) the conductor, gradually cohered into a small circle. Young people like to gather here to listen to bands sing. The Central Academy of Drama is also nearby, and there were many film and television companies and cultural-media publishing institutions. Many times, this group of friends would go to a show together, and the “Jianghu” bar was a place they often went to.

“At least during the ten years from 2005 to 2015, this area was the heart of Beijing’s independent music and live performances, attracting the most prestigious independent musicians in Beijing, as well as young people who love fashion and fresh sounds.” There were articles describing it in this way.

On December 18, 2022, reporter Yang Liu and her boyfriend Lin Yun were arrested because they had gone to the Liangma Bridge mourning site. As early as when he was still in college, Lin Yun and his friends had opened a small bar called “Not the Second Tavern.” Lin Yun was also a talented musician.

One friend who often went there remembers that its style was very literary, a bit like the style in Hong Kong in the 1980s and 1990s. Many wines were named after songs or places. Different from commercial bars, there would be activities like reading poetry, watching movies, and performances on the terrace. She remembered that a feminist-themed movie “It’s Happening” was shown in the tavern, which impressed her deeply.

This friend was the first in the group to get to know Yang Liu. Yang Liu was a reporter, and her writing was very good. They became friends and often interacted in broader friends’ circles on social media. Later, they met and became face-to-face friends as well.

Looking back now, Pengpeng feels that the reason why she liked Beijing the most is because of these different communities. But in 2017, Beijing cracked down on the “low-end” population and cleared out many of these interesting spaces in the hutongs. Coupled with the three-year strict COVID shutdown, many people have left, and many spaces are slowly dying. But Pengpeng feels that Beijing still has this kind of rich, textured scene. More importantly, there is still a community of friends.

“Our destiny is linked.” In January 2023, remembering those friends who lost their freedom, one friend put it thusly.

November 28, 2022 (Beijing): At the memorial gathering for victims of the Urumqi fire, someone in a car holds a blank piece of paper to protest. Thomas Peter/Reuters/Dazhi video.

5. “A group of people who identify with activism”

After learning that Zhai Dengrui (everyone called her Dengdeng) had been arrested, A Tian went to search, and discovered that she and Dengdeng were both members of several social-media groups, most of which were concerned with the epidemic.

A Tian is currently studying for a Ph.D. in anthropology, and only left Beijing in September, 2022. Cao Zhixin and Zhai Dengrui, who lost their freedom at roughly this time, were all her friends. “If I were there, on the night of November 27th, I would definitely be with them,” she said. She also felt that his fate was connected with theirs.

“The friends who were arrested at that time, they have a lot of feminist consciousness, but in fact their concerns are not limited to that. They are all compassionate and active young people. Facing inequality and injustice, for them, it’s all about first participating and then discussing,” A Tian said. In this sense, she believes that they are first and foremost activists.

A Tian recalled the last time she spoke with Deng Deng. Because that day she had just participated in an exchange on the Internet, and the topic was “lying down” [a growing movement at that time in China by young people to abandon the high-pressure demands of job and family]. A Tian asked Deng Deng: “Are you planning to lie down now?” She said that there is no way to do so yet. “I think most of the reasons I can’t have to do with economic factors.”

Denden is from Baiying, and from a good family. She first went to Fujian Normal University for her undergraduate degree, and then went to Beijing Foreign Studies University for a graduate degree in Comparative and World Literature. Before being arrested, she was an “online teacher.” Her friend Li Siqi, who was also arrested at this time, once wrote about Deng Deng’s working experience.

After taking his graduate degree, Deng Deng first tried to work in the teaching and training industry, and later, because of the “double reduction” [a Chinese-government crackdown on that industry in 2021, at least nominally to reduce the burden on students] she took up live online broadcasting to sell supplementary teaching books. Her friends were very surprised. How could Deng Deng, who loves reading so much, do live online broadcasting? But Deng Deng himself really enjoyed herself.

One friend, Xiao Ke (a pseudonym), later recalled that Deng Deng said that this was actually an opportunity for field research to learn what many parents think. Deng Deng has a wide range of interests, and she is very interested in drama, so she decided to apply to the drama major at the University of Oslo to continue her studies.

As A Tian sees things, these friends of hers are not from bad families. They work either for the state or for companies with substantial links to the state. After their arrests, it was very difficult to contact their parents. Most of their parents’ attitudes were “trust the government.” It can also be seen, she says, that “their communication with their families is insufficient.”

A Tian remembers that after the Spring Festival in 2022, she contacted a few friends who were studying in the social sciences and wanted to investigate some mines producing non-ferrous metal in the south. Four or five of them went together. They chose several mines in Chenzhou, Hunan, and Cao Zhixin was among those who went. Hunan province, recall, is where she is from.

“She’s very outgoing, and she’s fairly tranquil, not nervous. Although it hasn’t been long since she graduated, she can confidently communicate with the people she interviews,” A Tian recalled. “Although we were not familiar with each other before, we could chat easily. And we all have some sympathy for underdeveloped regions in China.”

A Tian believes that Cao Zhixin studies environmental history, and “she really cares about the environment.” They once talked about the difference between these non-ferrous metal mines in southern China and the coal mines in the north. It is said that the coal mines in the north can at least bring benefits to local farmers, while the non-ferrous metal mines in the south are all state-owned, and the local people get nothing from it.

They wanted to study those underdeveloped places, the south that given local historical, geographical, and environmental factors is not so “southern.” And in this kind of exploratory fieldwork, A Tian discovered that Cao Zhixin could chat with people in a natural and “reasonable” way. “She did all this out of simple curiosity and concern for society.”

They went to a uranium mine together and found a widow’s village. Here, all the miners of the first generation of the “prospecting team” had died of silicosis. After they got sick, they were perceived as belonging to the lowest stratum of residents in the village. If this kind of thing were to happen in her own home area, “Most people wouldn’t want to meddle in other people’s business, wouldn’t go. But she went,” A Tian said.

In 2020, A Tian, who had been studying, “wanted to get in touch with real society.” She once worked as a reporter for a news agency for half a year, and Qin Ziyi was the one who hooked them up.

In A Tian’s view, there are too many problems in China, and her friends, including Cao Zhixin, Qin Ziyi, and Zhai Dengrui, are all concerned about these problems. Some of these friends wanted to focus on combining smaller news stories. “They all have an organic awareness.” In her eyes, these friends are so young and enthusiastic, and they believe in “activism”. They care about the specific injustices at hand, and at that time they also felt a sense of empowerment.

“Fundamentally, they are all good students who have been fully educated, and they are a degree removed from the broader society,” A Tian said. Based on A Tian’s own experiences, she believes that for these “good students,” there will also be some skills and tools they possess that separate them from society, such as their academic achievements. However, they are always driven by a force that may complicate the lives of people educated like they have been. For example, they hang out in the aforementioned private spaces, they ask hard questions, and they participate in volunteer work. A friend of A Tian’s acquaintance once went to a nursing home for interviews during the Shanghai COVID surge in early 2022 and wrote a first-hand account of what she saw.

“Once you start paying attention to society, you will quickly find like-minded friends. Through articles, etc., some relationships will be formed.” In fact, in Beijing, there were more such gatherings, and there were always some common topics that would catch their attention. These issues had to do with the broader theme of “social injustice.”

A Tian believes that, for her generation, although the “1989 movement” was shocking, it was not a great injustice they personally experienced. For this group of people today, when they stand up, they are not acting because of ideology, but because of a very simple sense of righteousness, and they are all willing to transcend their fears. “They have the ability to overcome the surrounding social apathy, and don’t surrender easily. But at the same time, they are very inexperienced.”

“For them, life is extremely important. But except for a few among them who participate in social affairs a good deal, they have a disposition partial to the subculture,” A Tian said. But he also muses, “This is not any kind of contradiction. Most young people do not pay close attention to social affairs. To specifically act is a matter of happenstance.”

“In today’s China, no matter what you do you will be repressed. But as long as there is injustice, there will always be resistance. You will ask yourself, why is China such a ruthless land? Then, you will think you want to do something,” A Tian said.

November 27, 2022 (Beijing): To mourn the victims of the Urumqi fire, citizens light candles. Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

6. “These days of being confined, it’s not much different from war.”

Before the frigid winter of 2022, friends who had been separated from each other due to the epidemic reunited after a long separation.

Young people are always delighted to get together, but the overall mood was still “too depressing.” The zero-COVID policy that began in 2020 would be more stringent in 2022. At the beginning of the year, Xi’an was first closed for a month, and then Shanghai was closed for more than two. Throughout China the closure of cities become routine, as did nucleic-acid COVID testing of all employees, and the imposed “administrative stasis” of the whole city [a term used to denote extended closures of most businesses and government offices, along with confinement of most to their homes] at every turn. They were mired in this and felt the absurdity of it every day.

“Yuan Jing said that once, she waited in line for four hours in the cold wind and heavy snowfall to do a nucleic-acid test,” Pengpeng said. When friends got together in private, they also talked about the topic of “running away” [literally borrowed from the English “run,” and referring to fleeing the country] because to go through this was too depressing.

On May 11, 2022, a friend posted on Weibo: “The Nan Xin Yuan district of the town of Nan Mo Fang has ordered all households there to go to the quarantine hotel, no exceptions. The residents have not been told how long to quarantine, nor whether their apartments will be disinfected while they are gone. Since May 8, all residents in the neighborhood have not left their homes for a long time, and subject to daily door-to-door COVID tests. Suddenly they are worried about being exposed to the virus while being transported to the quarantine hotel. Many residents have difficulty moving, many residents are in late pregnancy, many households have newborns in their homes. Now they are objecting. We hope the local authority will reconsider its decision.”

This Weibo post vividly described people’s normal lives during COVID. Xiao Ke later learned that Yang Liu’s landlord had been threatened by authorities because of Yang’s criticism of the quarantine policy on Weibo.

In Xiao Ke’s eyes, Yang Liu is a journalist with a strong sense of responsibility, and a beautiful young woman. She likes to write poems and wear makeup. Sometimes, her boyfriend Lin Yun would turn Yang Liu’s poems into songs. On one album, there are two songs dedicated to her. There is a song called “Funeral Party.” Yang Liu wrote the lyrics and Zhai Dengrui sang it. “It’s very catchy.”

Xiao Ke said this group of friends are all very close and have their own opinions. Yang Liu studied social work at South China Normal University as an undergraduate, and was later accepted by a university program in Singapore offering a master’s degree in education, where she could have stayed after graduation and everything in her life would then stabilize. But because of her love for writing, she felt that she could not abandon her own cultural soil, so she returned to China and became a journalist. She likes to take excerpts from books and put them in a binder, and in recent years, her writing has gotten better and better.

The absurd and painful things that happened during the epidemic constantly stimulated these sensitive minds. Xiao Yi (a pseudonym) remembers that they had a friend, the founder of the Beijing Center for Mindfulness, named Dalida, a native of the former Yugoslavia. Dailda came to China in the 1990s. She was only 10 years old during the war. Today, she has witnessed the COVID shutdown in China and also said that there are not too many differences between the shutdown in China and wars. They both bring fear and sadness.

Xiao Yi said it made her suddenly understand that in this environment she finds herself in, she and her peers are, in essence, no different from refugees. “I also understood my own position better. All this that I have suffered, experiencing this long shutdown, is actually a war without gunpowder.”

She thinks of Li Yuanjing, a woman who was not in the least “political.” “She was just better off financially and sometimes hung out with people. But she was arrested because she was a group admin on Telegram.” Yuanjing was planning to go to school in France. She grew up well. But she was taken away for the first time on November 28, and when she returned, she had said she could only eat [soft] steamed buns and her feet were purple and always cold.

She remembered that December 22 was her birthday, and originally wanted to celebrate her birthday at the “Not the Second Tavern” and sent a message to everyone saying so, but this wish was never fulfilled.

Because her friends have not heard anything from Cao Zhixin, her recorded video suddenly went viral on January 16. Her boyfriend saw it and felt so dazed that he “didn’t have the courage to watch it.” He remembered that the day she was arrested for the second time by the police, he was in the Western Hemisphere and had to catch a prearranged flight, which was delayed by a blizzard. By the time he got off the plane, he knew she had lost her freedom.

He missed them. When they went to the Liangma Bridge that night, they were just there with love, unsuspecting.

On January 26, 2023, the fifth day of the first month in the lunar calendar, some of the friends who were imprisoned met with their lawyers, while others were still not heard from.

Epilogue: “Not the Second Tavern” later reopened. The group of old friends are not to be seen there. In particular Lin Yun and Yang Liu do not come around anymore. But the “baby” in the tavern, the little blackboard, was restored.

The tavern, first opened in Gulou, later moved to Sanlitun due to Beijing’s policy of “opening the wall and digging holes” [forcibly changing the urban landscape]. It is said that after the blackboard was moved, the stairs where it had sat were demolished.

The blackboard had a few lines of poetry, among them:

“Even if tomorrow morning the muzzle and a blood-drenched sun

Forced me to give up my freedom, my youth and my pen

I would never give up this night”

The lines come from Bei Dao’s “Rainy Night,” which was written on the day the tavern opened in 2014.