By Bradley A. Thayer

Commentary

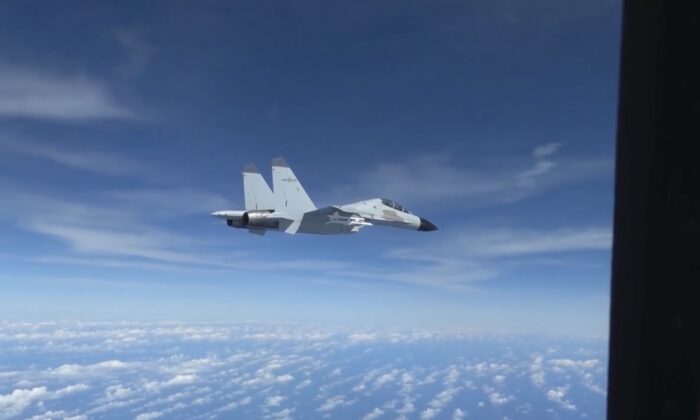

The near collision over the South China Sea on Dec. 21, 2022, between a Chinese J-11 fighter aircraft and a U.S. Air Force RC-135 Rivet Joint Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance aircraft compels the recognition that an incident at sea or in the air between Chinese and U.S. forces might lead to a rapid escalation of the incident. This incident requires that the analytical community consider how another kinetic Sino-American war might commence.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been at war with the United States since it came to power in 1949, and the Sino-American security competition remains high today. There truly is a Sino-American cold war.

However, there have also been hot wars with China—the United States has fought two wars with it. The first was in the Korean War, where the U.S. and other UN forces fought the “volunteers” of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The second was in the Vietnam War, where Chinese forces manned anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) sites and aided in the bridge, rail, and road reconstruction during the U.S. Operation Rolling Thunder air campaign against North Vietnam. During the Vietnam war, these AAA sites downed many U.S. aircraft, and U.S. flak suppression killed their Chinese crews, as did the bombing of the North Vietnamese transportation network.

There were many other incidents during the Cold War, particularly during the Taiwan Strait Crises of the 1950s and during the Vietnam War when China shot down U.S. aircraft that strayed into Chinese airspace—principally Hainan—including A-6, F-4, and F-104 aircraft.

China also downed U.S. ISR aircraft in international airspace, while there were occasions when U.S. aircraft also downed Chinese aircraft.

This history reminds us that war with China is not something new for the United States. Former CCP leader Deng Xiaoping identified the United States as the major threat to the regime after the fall of the Soviet Union.

A Sino-American war might start in three broad scenarios that would serve as the proximate causes of the war. The deeper causes of a Sino-American war always will be found in the aggressive leadership and ideology of the CCP, and the change of the relative balance of power in China’s favor.

First, it might grow out of an incident like the one last month. An incident in the air or at sea might lead to rapid escalation by the Chinese regime.

Second, it might grow out of the regime’s war against a U.S. ally or partner that compels a U.S. response.

Third, it might be a limited or major attack against U.S. territories like Guam or the United States itself.

Each of these offers a direct path to conflict. There is concern over the first because an incident may rapidly escalate and will always be impacted by Carl von Clausewitz’s identification of the importance of the “Fog of War” and the role of friction in military plans. That is, Clausewitz understood, first, that there will always be an imperfect understanding of the events surrounding a crisis or what is happening on the battlefield. Second, he grasped that military events would not proceed as planners anticipate, and so there must be the appreciation of failure—a military’s carefully developed plan may not survive contact with the enemy, as Prussia’s and later a united Germany’s Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke (the Elder) wrote. Third, he understood that clashes or limited wars tend to escalate.

Unfortunately, in its strategic thought and practice, the PLA does not possess the same understanding of these genuine risks and dangers. This is worsened by the fact the PLA is an unprofessional politicized military and so lacks the professional safeguards that the U.S. military possesses. That places the present Sino-American relationship in peril. Due to their lack of appreciation of these factors, the Chinese regime might execute a strategy of escalation after an incident.

Military delegates stand in formation after the commemoration of the 110th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution, which overthrew the Qing Dynasty and led to the founding of communist China, in Beijing, on Oct. 9, 2021. (Noel Celis/AFP via Getty Images)

Aggression against a U.S. ally, like Japan, would compel a U.S. response due to the treaty obligations of the United States. The concern is that an unprofessional PLA stumbles into a conflict with Japan. Against partners like India or Taiwan, the certainty of a U.S. response is not guaranteed. So the PLA might move beyond their coercive diplomacy against New Delhi or Taipei to execute a limited aims attack, as China did in 1962 against India, or launch a major war. There is always a possibility that a border clash against India, as occurred in 1967 and more recently in 2020 and 2022, or an incident at sea in the Taiwan Strait will provoke escalation. While New Delhi possesses nuclear weapons, Taipei does not, so the absence of a U.S. extended deterrent commitment to Taipei makes a Chinese attack more likely.

Finally, the United States cannot dismiss the possibility that the Chinese regime executes a “bolt out of the blue” limited or major attack against Guam, Hawaii, or the mainland. The prodigious growth of China’s conventional, hypersonic, and nuclear capabilities—while the United States has been in a strategic catatonic state—makes this once incredible possibility one that is entirely within their capabilities.

There are many paths to a hot war with China. Were it to come, the particular road would be chosen by the leadership of the Chinese regime. Increasing belligerence against Taiwan suggests that the world may be on that road soon enough. Lamentably, incidents like December’s J-11/RC-135 near collision remind the world that the Chinese regime is aggressive and that the Chinese military encourages unprofessionalism. This makes the likelihood of an incident a certainty and the escalation of an incident increasingly hard to discount.

This article first appeared in the Epochtimes on Jan 3, 2023