By Jianli Yang & Evan Osborne

If the Chinese people today could legitimately vote as a whole, they would, alas, probably not choose those with genuine skill in governance. Instead, they would repeatedly choose leaders who would abuse them while claiming to act in the name of the people. And when Chinese actually lack voting rights, how can they have any hope at all? This is precisely the circumstance China now faces. Given this, ever-more Chinese are taking the option of voting with their feet.

Emigration worldwide has at least two motivations. The first is to be pulled elsewhere by opportunities for emigrés or their families to live better, for example via better education for their children, more rewarding work, or the ability able to live in a superior society overall. For the talented in particular, who think they are capable of competing with the global elite, emigration can open the door to things that are available only outside China. For Chinese at the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first centuries, these themes were frequently discussed.

Another sort of emigrant is driven by the desire to escape catastrophe, e.g. war or dictatorship, as has been the case with Syrians, Burmese, and many others. Those leaving Xi Jinping’s China, who used to substantially be driven by the first motivation, are now increasingly driven out by the second. The Chinese have an ancient saying in this regard: The self-respecting person does not wish to live a walled-in life.

Using the slogan of the rule of law to trample on its actuality; the disappearance of righteousness in government

Since coming to power in 2012, Xi Jinping has launched a series of campaigns nominally about fighting corruption but actually aimed at eliminating political opponents and establishing his political prestige. As of April 2022, the national prosecution authorities had filed a total of 4.388 million cases against a total of 4.709 million officials at all levels. And the outcome usually has nothing to do with whatever actual guilt there is; extorting confessions by torture is a common tactic used by authorities to dispose of cases promptly. Chinese society has always been one of the rule of man and not the rule of law, and powerful officials at all levels have long been accustomed to leaving no stone unturned in extracting wealth. But they have always only done this within their fiefdoms. But now such officials have seen the rules change, from them playing games with the law themselves to being the victims of such games by others higher in the hierarchy. For those who have gone from waging arbitrary power without fear to fearing being a victim of the arbitrary power of others, the contrast must leave them completely shattered. According to statistics, from 2012 to 2019 more than 260 senior political and business officials in the CCP died unnatural deaths.

It is futile to even try to eradicate this kind of institutional corruption as long as the overall political system remains unchanged. The vast majority of officials have skeletons in their closets and are thus as fearful as lambs waiting to be slaughtered. And so even if they cannot emigrate themselves due to unyielding party rules, as is true for increasingly many, they frequently arrange overseas escape routes for their family, especially their children. Likewise, there those without government posts who nonetheless can be declared an enemy of the people at any time, whether they are businessmen who have paid bribes to such officials or socially prominent “villains” who because of personal mistakes might be the target of blackmail. They too dream of escaping the risk of arbitrarily becoming targets of Chinese “law,” of what happened to the pianist Li Yundi happening to them.

The widespread arrest of human-rights lawyers on July 9, 2015 told the Chinese people all they needed to know about the Xi regime’s comprehensive crackdown on previously budding civil society. The public-security department arrested, detained, and interviewed hundreds of lawyers, human-rights defenders, petitioners to the government (such petitions having since ancient times been part of Chinese tradition) and their relatives on a very large scale in 23 provinces, and threatened even more dissidents and their relatives with house arrest, imposed restrictions on them leaving the country, and on top of that created various more mundane life obstacles.

The CCP authorities stipulate various legal crimes, but do not bother implementing procedural safeguards to promote justice, and thus blatantly violate the most basic human rights. These campaigns are not only a persecution of a few unlucky individuals. Because they can happen to anyone at any time they are also a violation of the rights of society as a whole. In 2015 those Xi could deem troublemakers started to face the prospect of his wrath, and even the inherent identities of people like them — human-rights activists, dissidents, liberal intellectuals, members of ethnic and religious minorities and others — made many targets, and they chose to flee. And among those who stayed, many were oppressed, including through cruel incarceration.

According to The Economist, citing data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, from the year Xi took power in 2012 to 2020, 613,000 Chinese applied for asylum in other countries, the annual number growing 13-fold between 2010 and 2020 and by far the highest for any country. In Hong Kong in particular, helped by offers extended to some in its former colony by the British government, the population has recently decreased by 1.6% in the last year alone. The lessons are that when political power is wielded arbitrarily and mercilessly, the rule of law that people rely on to live and work in peace disappears, and they seek to shelter themselves to the extent they can and, if they cannot, seek to escape.

Using arbitrary administrative power to destroy the economic rules of the game — how the “common prosperity” campaign threatens economic freedom

For the economic elite, accumulating wealth and creating social value through commercial means is how they pursue self-development and self-improvement. And this requires a stable, orderly, legally protected market environment in which to do business. The Xi regime has forcibly intervened in the economic order through bureaucratic means, as if it had divine authority. In the past few years, it has tightened control of Internet finance, suppressed the real-estate industry, dramatically repressed the previously flowering education/training industry, and strongly pressured other industries. The resulting widespread business closures and large increases in unemployment have caused confusion among economic elites, both with respect to investment and internal management. Will disasters that happen today in other industries happen tomorrow in their own? Previously in China’s era of openness and reform, when major policies were by the CCP’s historic standards relatively stable, it was possible to triumph over competitors and achieve market success through taking risk, taking as given the principles of competitive markets. But that is no longer true. Making these decisions now, under the shroud of power ruthlessly and arbitrarily exercised, is a fool’s errand. Under such circumstances decision-makers lose their ability to predict the future, and naturally also their willingness to continue taking risks, to invest, even to operate at all.

And Xi’s raising of his “common prosperity” agenda at the end of 2021 has raised fears about his possible desire to fulfill communism’s promise to eradicate private ownership. If continuing to operate becomes a gamble, then merely protecting one’s existing wealth becomes people’s bottom line. According to estimates by the UK investment immigration consultancy Henley & Partners, 10,000 high-net-worth residents in Shanghai intend to withdraw as much as $48 billion in wealth from China this year. For the economic elite, a successful business decision comes from 90% information and 10% intuition. And arbitrary economic repression means that actually useful market information is increasingly difficult to come by. Under the current situation, as business leaders see it the withdrawal of wealth becomes a lamentable but essential decision.

The Covid-19 madness as the destroyer of both people’s lives and their wills

The sudden, cold-blooded closure of Wuhan in 2020 has received praise in some quarters, but the quixotic anti-Covid measures in Shanghai in spring, 2022 have thoroughly demonstrated the CCP’s disconnect from reality. China’s most elegant and cosmopolitan city, at the mercy of the country’s strongman in Beijing, quickly fell into a catastrophe in which all networks its people relied on to live were severely, sometimes permanently disrupted. Officials at all levels, who should have been responding to the people’s desperate needs, instead used such power as they had, sometimes out of fear for what would happen to them if they did not, to create a nightmare for the city. Residents’ dignity was crushed by forces they could do nothing about, in front of their parents and children, so that even people’s most basic human responsibility, to protect their families, became impossible. People were in essence imprisoned, deprived of most of what makes life worth living, and humiliated by those with the power to do so. The economic collapse caused by the lockdown has left countless people without jobs and income. Statistics recently released by the National Bureau of Statistics show that in the first half of 2022, unemployment in Shanghai reached 8.9%, the highest in the country, and increased to 12.5% in the second quarter, the peak period of the city’s closure. City shutdowns similar to Shanghai’s abound even now, all over the country. In April, when Shanghai went into lockdown, 373 million people in 45 Chinese cities, or about a third of the country’s population, were already under some form of lockdown, Japan’s Nomura estimates.

According to Xi and his propagandists, the task is to fight the virus, to prove the wisdom of the CCP, whatever the cost! This government slogan is perhaps stirring the first few hundred times one hears it, but when one personally pays the price, these abstract ideological jeremiads destroy the lives of flesh-and-blood people. The novel coronavirus makes a mockery of the pretense of policymakers, and the raging of the CCP’s associated political virus has become the last straw that will crush the Chinese people’s aspirations. And when it comes to the loss of China’s best and brightest, the past is prologue. Recently, the number of Chinese Internet searches for “emigration” has surged, with the number of searches so far reaching nearly 50 million.

For ordinary middle-class families, leaving home does bring the difficulty of reorienting their lives in an unfamiliar environment, but for more and more Chinese this seems to be a price worth paying given the one they are paying now in the never-ending zero-COVID China. If one wants to create a better future for oneself, one must work hard, without relent. But when autocratic rulers use a twisted ideology to destroy social solidarity, and the minds of young people in particular, they conceal the arbitrary manipulation and plunder of the majority by the minority (the costs of both frequent testing and forced confinement are often borne by the victims themselves) and make it impossible to see a better future.

The Chinese government’s monopoly on public expression and on education was able to blind people for a time, but exercising absolute power without restraint is driven by its own internal madness, eventually exposing its ugliness. As propaganda fails and more and more people obey merely out of fear, the call to freedom grows stronger.

Of course, for most people emigration, especially from a totalitarian society, is not a lighthearted matter. It takes a long time to overcome language and cultural differences, and to establish a new framework for living, a new identity. Most people retain deep psychological attachment to where they live, and know there are some, perhaps most, friends and family members they will not see again. The routines of life that gave them comfort must be discarded. This is what is lost in the course of gaining freedom.

So for many Chinese, the surge of both actual and contemplated emigration under Xi’s regime is the result of having to choose the lesser of two evils. If a great deal of chaos in their lives is to be expected in the short term when they leave, forbearing Chinese who leave will endure, wait, and hope to meet those they left behind in the future.

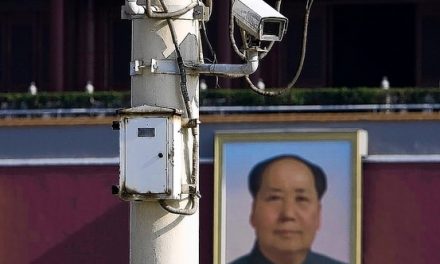

In the ten years that Xi has been in power, not only has the country’s situation not improved, it has continuously darkened. The arbitrary rewriting of the constitution at the Communist Party’s 19th National Congress showed Xi’s determination to maintain for years to come his hold on power, supposedly to “serve the people.” On July 27, leading provincial and central cadres gathered online and dutifully expressed the need to “study the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important speeches, and welcome the Party’s 20th National Congress.” The session produced a resounding call for Xi’s re-election at the Congress meeting this October. And so too at the July 28 Politburo meeting, the importance of Xi’s “dynamic clearing” — where any positive result from the COVID tests Chinese are forced to undergo several times a week throughout the country leads to solitary confinement — and the political centrality of epidemic prevention and control were again emphasized. These words mean that the Chinese people will not only have to endure the normalization of what was once abnormal epidemic prevention, and the enhanced monitoring of every aspect of their lives, with all that implies for the ability to monitor everything they do, but also accept the reality that the associated political virus — the belief that this will be forever necessary to preserve the party’s stranglehold on power — is now itself endemic.

And so for many of China’s brightest and most industrious, a future life in such a China is finally, if reluctantly, unacceptable. In the last ten years the invasion by totalitarian power of both social and private life in China has increased without relent. The caging of free thought by ideology has become comprehensive, and Xi’s decision-making style has become more and more uncompromising in its willfulness, irrationality, and inhumanity. With his expected seizing of a third term in a few months, people’s expectations for the future continue to decline, and the number of people who vote with their feet, already growing, is bound to grow further. These new emigrants are escaping a feeling of helplessness and hopelessness about what would be their futures if they stayed. In escaping they will take their talents and wealth with them, but also their frustrated desires to help create a better China. These are the people China can least afford to lose.

This article first appeared in the Real Clear Policy on 9/7/22