by Bradley Thayer Lianchao Han

Jack Ma, the richest man in China and founder of Alibaba, oddly vanished from public view for nearly three months only to reappear recently on a homemade video, promising “to meet again after the pandemic is over.” This indicates that, unlike other less fortunate wealthy businessmen, Ma is safe for the time being.

However, it does not mean Ma is out of danger. Ma is a vocal billionaire who has been popular as well as controversial in China. His unexplained disappearance raised suspicion that he might be detained by China’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), the highest internal enforcement institution of the Chinese Communist Party, of which Ma is a member. There is ample precedent for this. Many Ma’s fellow wealthy entrepreneurs disappeared in CCDI’s jails for long periods of time, only to resurface before one of the “people’s courts,” before sentencing. Wu Xiaohui, the grandson-in-law of China’s late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, and Chairman and General Manager of Anbang Insurance, was sentenced to eighteen years in prison and his property of RMB 85.7 billion was taken from him.

It appears Jack Ma may have landed relatively softly and will not suffer the same fate as Wu. But his troubles are far from over.

At the time of his disappearance, we know that Ma was about to reach his career peak by launching the world’s largest initial public offering of Ant Group, his financial technology company. On Oct. 24, 2020, Ma delivered a speech at the Shanghai Bund Financial Summit in which he openly criticized China’s financial regulatory system for being obsolete and hinders and stifles innovation. Subsequently, Ma’s speech went online, triggering a heated debate.

It was reported that he was soon summoned by China’s regulators and reprimanded. On Nov. 3, two days before Ant Group’s scheduled IPO in both Shanghai and Hong Kong, the Chinese authorities stopped the IPO altogether. Subsequently, China’s central bank official financial stability bureau director, Sun Tianqi, criticized third-party internet financial platforms like Ant Group’s, accusing them of illegal financial activities, similar to “driving without a license.” This triggered Ant’s quick removal of its online deposit products. But it failed to stop the authorities from launching an investigation into monopolistic conduct of Ma’s platforms in late December. On Jan. 15, 2021, the government ordered Ant Group to establish a rectification work team with the guidance of financial regulatory authorities to change its business operations.

The government’s actions against Ma raises the critical issues of why the regime targeted Ma and his successful businesses, and the message it intends to send by disciplining China’s richest man.

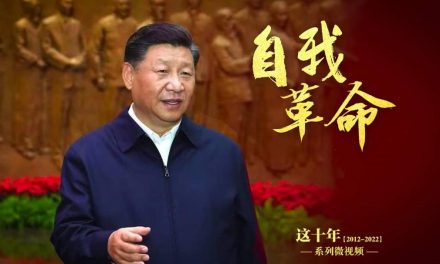

It appears that Ma had to endure his ordeal due to China’s leader Xi Jinping’s insecurity and paranoia. Xi will not tolerate rivals, or potential rivals, emerging to challenge his position. Finance is one of the most critical pillars for the CCP to maintain its totalitarian rule. It is notable that three years ago, Xi, for the first time, alleviated financial security to a critical part of regime security in the 40th CCP Politburo study session. He demanded that the Party must have firm control of China’s financial sector, prevent systematic collapse by eliminating all possible risks.

Thus, the recent actions against Ma and his Ant Group is the implementation of Xi’s order “not to neglect a single risk factor or . . . hidden danger” in the financial sector. In an interview published by China’s official media Xinhua, Pan Gongsheng, deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) revealed that the measure came from the CCP top, aiming at intensifying China’s anti-monopoly efforts to rein in so-called “disorderly capital expansion.”

Ant Group’s business model focused on providing payment and deposit platforms for the so-called “low-end population,” essentially the poor, who could open accounts with a deposit of fifty Yuan, which is less than $8. It also doubled the interest payment than big state-owned banks. The higher returns at lower entry thresholds allowed Ant Group, and its small local bank users, to accumulate a large amount of capital rapidly. Xi fears that this large sum of capital in the hands of private companies could be potentially used by the opposition, endangering his grip on power. Therefore, the risk must be eliminated.

Ma’s innovative platforms now provide small and micro-financial services, which big banks disdained to do originally. They allow local banks to solicit deposits nationwide which has made the big banks jealous, believing that Ma stole their profits and customers—and harmed their interest.

Xi has taken radical measures to ensure China’s state-owned enterprises are “stronger and bigger” since he took power because he inherently dislikes private enterprises as he believes them to undermine the socialist economy. Although some CCP princelings are involved in Ma’s business, it is a private-owned company and one that grew rapidly to control enormous resources. For example, last year, Ant Group, which Ma owns a controlling interest, had over seven hundred million monthly users and made $17 trillion payments. Ant’s digital finance technology platform raked in a $300 billion credit balance and managed $590 billion assets with a fast growth rate of 40 percent and a high-profit margin of 30 percent. From the CCP’s perspective, Ma’s behavior is getting worse as he is also expanding his business to media and entertainment, which are heavily ideological and thus industries that the CCP guards closely. Also notable is that the big data obtained through Ma’s payment and financial technology platforms is invaluable for the CCP to gather more information about the Chinese people in order to tighten their control of the population as well as its global reach.

Xi will never allow Ma or any individual to possess such enormous resources and power, despite the fact that Ma expressed his willingness to give his business to the government. Xi follows Russian president Vladimir Putin’s Yukos playbook, and uses anti-corruption as a cover to confiscate many of the super rich’s assets and transfer them to state-owned companies. Xiao Jianhua, a Chinese-born Canadian financier was kidnapped from Hong Kong’s Four Seasons Hotel and disappeared for over three years. Last year, the Chinese government snatched his company and its $150 billion assets. It is unclear if Ma will suffer the same fate as Xiao and Wu but it is certain that Xi is now using antitrust to break Ma’s business and place it under CCP’s tight control.

The unfolding story of Ma indicates Xi’s vulnerability and concern about the financial sector and demonstrates the perils of being “Crazy Rich Chinese.” For regime security, he chooses control over innovation. As Xi crushed the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, favoring control over wealth creation, he will continue to crack down on China’s private entrepreneurs and weaken the private sector to ensure state enterprises’ monopoly in key sectors. For Western interests, any future trade negotiation to open China’s financial market is an illusion.

This article first appeared in National Interest on January 30, 2021