BY JIANLI YANG – 06/18/21 6:00 PM ET

China’s anti-corruption campaign continues in full swing as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) prepares to celebrate a hundred years of its founding on July 1. The January death sentence imposed on Lai Xiaomin, former chairman of China Huarong Asset Management, for accepting bribes worth $279 million USD shook the Chinese bureaucracy, the latest corruption conviction among government and party officials. His execution reportedly has led to confessions from others for accepting bribes, but it was an unusual sentence for bribery and other financial crimes.

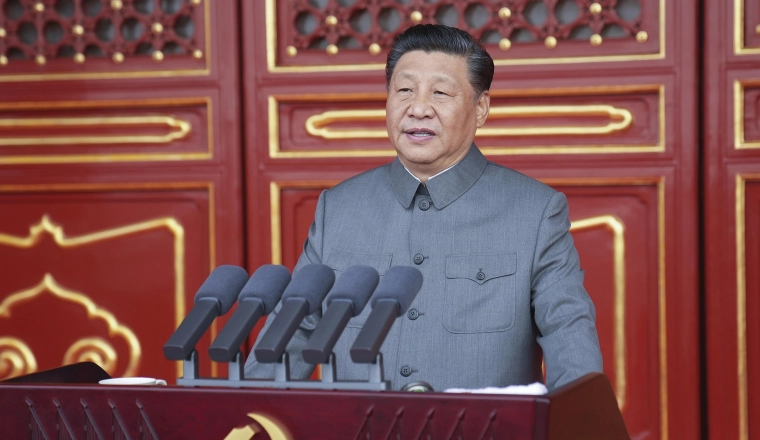

Thus, two contradictory strands are evident in China today — one of celebration and the other, retribution. As China’s global geopolitical prominence grows, its authoritarian tendencies are intensifying domestically. The party’s focus on survival is natural because, since its founding and the creation of the People’s Republic, Beijing has always attempted to reinforce CCP primacy. Consequently, everything positive that has happened in China since 1949 is credited to the party. A 1950s-era propaganda song popularized the slogan, “Without the Communist Party, there would be no new China.” That song could be sung today with a twist: “Without the CCP and Xi Jinping, there would be no Chinese Dream.”

Nikkei Asia reports that, in January 2020, the disciplinary committee decreed that any official who “voluntarily surrendered” in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign “would be shown leniency” and those who did not and continued accepting bribes “would be dealt with harshly.” Lai Xiaomin evidently was held up as an example of one who did not cooperate. The newspaper tweeted in May, “The number of government officials involved in corruption cases who turned themselves in jumped by half in 2020 to 16,000.” Several reports of officials surrendering have appeared in state-controlled media, apparently to show that Xi’s party control extends down to the lowest levels ahead of the 2022 Party Congress, at which he hopes to begin an unprecedented third term.

The other important aspect of China’s celebration is the focus on Xi Jinping himself, a “core leader.” As The Times of India recently reported, when Xi became party General Secretary in 2012, the CCP began promoting the “centenary goal” of achieving a “moderately well-off society” by 2021. Other goals included the elimination of poverty, building a space station, and becoming an internet power. All of this is tied into Xi’s “Chinese Dream,” which in some ways has found partial fulfillment today. Take, for example, China’s successful launch in April of a key part of its new space station into orbit and the landing of a rover on Mars in May. China also claims to have eradicated poverty in several parts of the country, including Tibet, leading Xi to declare in February the end of extreme poverty in China.

The positives are undoubtedly there, but the negatives loom large on the horizon. For example, at around $11,000 USD, China’s per capita gross domestic product is still far below that of other developed countries. More importantly, access to health care and education still eludes many Chinese citizens. And, as The Times of India reported in May, “For many Chinese people, especially ethnic and religious minorities, a succession of ideological crackdowns carried out by Xi and his hardline supporters has also cast a shadow over their futures.” The anti-corruption campaign, said to have punished more than 200,000 party cadres, could become a leading human rights concern within China.

According to an NPR report by Emily Feng, in 2018, Xi launched another type of anti-corruption with the slogan “Saohei chu’e,” meaning to “sweep away black and eliminate evil.” This campaign focused on businessmen and industrial house heads, NPR noted, giving province-level officials “wide discretion to prosecute local crimes with state backing.” The campaign cracked down on nearly 40,000 “supposed criminal cells and corrupt companies,” Feng reported, “and more than 50,000 Communist Party and government officials were punished for abetting them.”

Though it was supposed to end this year, the campaign appears to be continuing, as evidenced by the new confessions by party officials as the centennial celebration approaches. So, while the CCP prepares to celebrate, many Chinese citizens will continue to die. Reporting on the centenary preparations, the New York Times noted in April that authorities have stepped up efforts to limit dissent, signaling that officials know “the party must do more to strengthen public loyalty and fortify its control of society.”

This appears to be why the anti-corruption was begun in the first place — to fortify Xi’s leadership position and to ensure that no party dissent is visible. So much for 100 years of celebration.