By Bai Ding

June 16, 2024

Thirty-five years ago, the conjunction of unrestrained “official profiteering” within the system, in which people made huge profits without any investment, and the poverty of the laid-off and unemployed outside the system, aroused widespread dissatisfaction among the people in mainland China for the first time since the end of the Cultural Revolution. Thirty-five years later, the descendants of the former profiteering officials and the descendants of the former laid-off workers are still firmly fixed at the two ends of the social ladder passed down from their respective parents and other ancestors. (Note: “Official profiteering” is an informal economic term popular in mainland China in the 1980s, referring to powerful officials taking advantage of state monopoly of resources to exclusively sell or license those scarce materials, controlled by people in the state at high prices, to make huge profits. This term refers to both the rich and the powerful who profit from it, and the profit-making behavior itself.)

Thirty-five years ago, although China’s information technology was extremely backward, young Chinese people were able to absorb various knowledge from the outside world through the cracks. Thirty-five years later, although China’s information technology is at the forefront of the world, China’s walls are higher and more solid, and all young people can absorb is the rotten poison in the stagnant pool inside the walls, such a pool being unable to give birth to new life.

Thirty-five years ago, millions of young students with ideals and enthusiasm led in proclaiming the public’s dissatisfaction with the economic situation, and in political demands for freedom of speech, association, and the press. It was a qualitative leap. Thirty-five years later, although China still has warriors such as Zhang Zhan and Peng Zaizhou who go beyond economic demands and pay attention to the rights of the masses, today’s young people can only hold pieces of blank paper and be silent protesters, because they can no longer make a sound.

Thirty-five years ago, tanks and machine guns crushed the dreams of young people for democracy and freedom. The Chinese people were forced to accept the only means of survival allowed them by the Chinese government — trading political freedom for economic freedom. Thirty-five years later, the Chinese people, who have been deprived of their freedom, suddenly found that the wealth they had gained by giving up their freedom is also disappearing. Today’s young people seem to have gone through a lifetime of hardships and are exhausted. Under the heavy pressure of society, they are no longer able to fight, and can only “lie down” and survive.

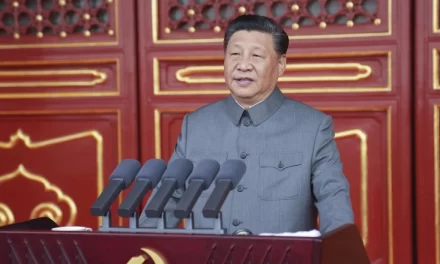

Thirty-five years ago, the relaxed stance emerging from within the CCP, represented by Hu Yaobang, gave people hope for democratic reform in Chinese society. Today, thirty-five years later, after Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao’s four consecutive “corrections” paved the way, Xi Jinping, authorized by the CCP, has done the (for them) sensible thing and re-sealed Chinese society, returning it to airtight iron barrel of control, as for most of the last 70 years. The CCP’s wishful thinking of reforming China’s system through its own will has proven to be nothing more than a fantasy that can never be realized.

But one thing is beyond doubt: the CCP cannot hold power in China forever. Whether the CCP peacefully withdraws from power like the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, is forced out of power by powerful warlords and plutocrats like the Qing Dynasty, or provokes international outrage by launching a war in the Taiwan Straits and its members scatter after the party leader is beheaded, Chinese society must face how to deal with its legacy, and reach an early consensus on China’s past crimes and how to deal with those involved in them, because these issues are historical obstacles that must be cleared before China can establish a democratic, legal and constitutional government. They are also historical wounds that must be healed before a widely prosperous society can be formed.

China is not the only country to have faced these problems. Prior to this, many countries from South Africa to Taiwan, from the Balkans to South Korea, from Rwanda to Chile and Brazil, had in the process of transitioning from military dictatorships to democracies faced the problem of how to deal with human-rights violations committed by the previous regime. Theoretical research aimed at solving this problem has formed the latest interdisciplinary subject in the field of contemporary international justice and human rights, transitional justice [1].

I

Since transitional justice or TJ has become an important part of and a focus of debate and research in the fields of international justice and human rights, it is crucial to clearly define the term.The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights officially defines “transitional justice” as follows: “TJ covers all processes and mechanisms involved in resolving the legacy of past large-scale conflicts, repression, violations and abuses, with the aim of ensuring accountability, justice justice and reconciliation.” [2]

The International Center for Transitional justice (ICTJ), the international headquarters of the movement, defines it more straightforwardly: “TJ refers to how societies deal with the legacy of large-scale and serious violations of human rights. It raises question about the law, politics and social sciences. It explores some of the toughest problems. Its focus is on the victims.” [1]

From this it can be seen that the complete meaning of the term transitional justice must include two core concepts: the transformation from an authoritarian tyranny to a democratic government, and justice for the victims of the former tyranny.

II

There are also huge differences between the two sides of the Taiwan Straits on how to accurately translate “transitional justice” [in the original article the English term has been used throughout] into Chinese. The term “transitional justice” consists of two words. If we only understand it literally, each word has two different meanings, and the compound phrase TJ can also have at least two completely different semantics. However, the above two formal definitions of transitional justice clearly eliminate this uncertainty over the term’s meaning, and then determine the core semantics of TJ: justice for the victims of tyranny in the process of transition from autocracy to democracy.

In 2001, Taiwanese academic circles first translated the word TJ as “justice during times of change” (“变迁中的正义”). The translation is a bit lengthy, and the use of the modifier “in times of change” makes the meaning of the entire phrase ambiguous. After nearly 20 years of research and debate, Taiwanese academic circles finally officially identified the Chinese translation of TJ as “transformational justice” (“转型正义”) in 2017 [3]. The Taiwan Executive Yuan Human Rights Information Network’s definition of “transformational justice” is also completely consistent with the two original English definitions cited above.【4】

But in China and most simplified-Chinese online platforms throughout the world transitional justice is translated directly as “transitional justice” (“过渡司法”), although here the characters for “justice” here are associated with judicial procedures rather than moral claims. Although this version directly translates the two words “transitional” and “justice,” it loses the two core concepts contained in the phrase “transitional justice”: the progressive change of political regimes and the pursuit of justice. This Chinese translation not only downplays the essential changes in the political system with the word chosen for “transition” (the chosen translation for “transition” really means “short-term, homogeneous smooth change”), but also limits the wide-ranging behavioral purpose of achieving justice. As for “justice” itself, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights clearly emphasizes in its definition of TJ: “These processes may include judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, including seeking the truth, prosecution, compensation and various other measures.” [2] It can be seen that China’s attitude towards transitional justice, as seen in the translation of the term, seriously deviates from the internationally recognized strict definition of it.

China’s mistranslation of transitional justice should not just be seen as Chinese translators misinterpreting the original text. It is more likely that the two core concepts of transitional justice are deliberately obscured according to the instructions of the CCP. The purpose of this is to avoid triggering thinking about and discussion of in Chinese society how to achieve justice in the current and post-CCP era.

Through the analysis of the above two Chinese translation methods, it can be seen that compared with the narrow translation, the other is more faithful to the meaning of the original text.

III

The implementation process of transitional justice in the proper international/historical sense involves many aspects of international law and human rights. In combination, these actions can be condensed into three stages: confirming atrocities; holding perpetrators accountable; and compensating victims. The ultimate goal of these actions is to achieve social reconciliation and avoid a recurrence of history.【5,6】

The concept of transitional justice originated in the late 1980s and early 1990s. At that time, South Africa, Argentina, Chile, and Eastern European countries began to transition from military and communist dictatorships to democracy. In the process, political groups and broad social movements were demanding disclosure of the truth about systemic abuses and human-rights violations committed by the previous regimes, and justice for the victims. They put the rights to truth, justice and reparation at the center of ongoing political change, calling for the foundations for more peaceful and inclusive societies to prevent the recurrence of such atrocities.

In 2000, with sponsorship by the Ford Foundation, human-rights activists began working together to explore the best strategies to address the legacy of massive human-rights violations and achieve sustainable peace. In 2001, the International Center for Transitional justice (ICTJ) was formally established and has now carried out work on accountability, achieving justice and building sustainable peace in more than 50 countries.

Some practices in transitional justice have been successful, while others are unsatisfactory. In Asia, South Korea is a country that has successfully implemented transitional justice. After thorough truth-finding, accountability and compensation, Korean society has healed the damage caused by the military dictatorship and established a democratic system of reconciliation and tolerance. Taiwan is an Asian country where the practice of transitional justice is incomplete. Although Taiwan’s transitional-justice process has publicly investigated and confirmed the harm caused to Taiwanese society by the Kuomintang during its military rule, and also compensated the victims, the important link of accountability is completely missing. This allows Taiwanese society’s historical grievances against the Kuomintang to continue to exist and exert influence on many major issues, becoming a lingering historical fetter.【7】

IV

Compared with the aforementioned countries that have successfully or semi-successfully realized the transition from military dictatorship to democratic government, China is not only still under the autocracy of the CCP, but the pressure imposed by it seems to be increasing day by day. The number of abnormal deaths of citizens caused by the CCP, the destruction of the traditional value system of the society, and the extensive and continuous human-rights violations against citizens far exceed that of any other authoritarian regime in the contemporary era. Therefore, no matter how China might get rid of the CCP’s autocracy, Chinese society will not be able to establish a sustainable democratic constitution and achieve true social reconciliation without fully and thoroughly disclosing the CCP’s atrocities and seeking justice for the its victims.

Given the practices and experience of many of the above countries in the field of transitional justice, what China needs to do is not to find its own way one step at a time, but to study the successes and failures of various countries to find the way to do the least harm to Chinese society, and bring the public the most long-term benefits. A lasting solution to justice should be found.

Realizing transitional justice in China or announcing plans to realize it should not just trace the CCP’s past crimes, but should also be used as a means to curb any new ones. If impunity for the CCP’s atrocities continues to be the norm in Chinese society, its atrocities will continue. In contrast, if members of the CCP’s violent system see the punishment that comes with past violations, they will hesitate before committing new ones because of the consequences they will associate with doing so.

It is only a matter of time before the CCP hands over power in China. Tracing its atrocities and violations through the transitional-justice mechanism, and using its accountability mechanism to deter members of the CCP’s violent system so that they are afraid of committing new violations and atrocities, will not only lead to China’s future transition from totalitarianism to democratic constitutionalism. It will be an indispensable link in the transformation process, and an important means to alleviate the suffering of the masses and dismantle the CCP’s violent machinery.

References

- Our Story : International Center for Transitional justice

https://www.ictj.org/our-storyyibaochina.com

- OHCHR: Transitional justice and human rights

https://www.ohchr.org/en/transitional-justiceyibaochina.com

- Cheng-Yi Huang, “Transitional justice Symposium: Law’s Liberation,” September 18, 2020.

opiniojuris.org/2020/09/18/transitional-justice-symposium-laws-liberation/

- 轉型正義,台湾行政院人权资讯网 ((Transformational Justice, Taiwan Executive Yuan Human Rights Information Network),

https://www.ey.gov.tw/hrtj/EC6E2006D780D3F8yibaochina.com

- Transitional justice EXPLAINED (INFOGRAPHIC).

https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/30518-transitional-justice-explained-infographic.htmlyibaochina.com

- Andrieu Kora, “Transitional justice: A NEW DISCIPLINE IN HUMAN RIGHTS.” SciencesPo, Jan 18, 2020.

- Jenny Wang,澆灌根柢:海外台灣人與轉型正義 (Watering the Roots: Overseas Taiwanese and Transitional Justice), Mar 4, 2019, Politics and Society, Ketagalan Media

This piece was translated from Yibao Chinese. If republished, please be sure to add the source and link https://www.yibao.net/?p=247861&preview=true before the text when reposting.

The author’s point of view does not necessarily represent that of this journal.